This glossary provides the terminology used in the Welfare Footprint Framework, together with their operational definitions. To differentiate these terms from their general usage, we recommend capitalizing them when referring to the definitions here.

Welfare: All affective states (negative and positive) experienced over a period of interest.

Welfare Footprint Framework: a scientific methodology for quantifying animal welfare by measuring the intensity and duration of animals’ experiences, both positive (pleasant) and negative (unpleasant) Built to reflect the full complexity of life in different animal production systems, the method considers the full range of, environments, and management practices to which animals are exposed, over their different life stages. The framework introduces innovative tools that enable transparent, evidence-based comparisons of animal welfare across interventions, systems, and food products (more information here).

Welfare Footprint: A quantitative measurement of the impact that actions or processes across different sectors have on animal welfare. These sectors include, but are not limited to, industrial, commercial, agricultural, research, and natural processes. Like in a life cycle analysis, a welfar footprint captures all welfare-relevant processes from birth to death for every animal involved—market animals, breeding stock, and ancillary species (e.g., fish used as feed). The metric quantifies three dimensions of animal experiences: (1) Intensity: How severe or pleasant each lived experience is (from mild discomfort to extreme pain; from contentment to intense pleasure); (2) Duration: How long each experience lasts; (3) Prevalence: What proportion of animals experience it. These dimensions are combined to calculate total time spent in positive and negative states of varying intensities. Results can be standardized (i) per unit of product (e.g., 10 hours of severe pain per kg meat); (ii) per person in a population; (iii) per unit of GDP, (iv) per dollar spent, among others, enabling direct comparison of welfare impacts between animal products, production methods, countries, companies, interventions, standards, or policy options.

Welfare Assessment (Guiding Principle): The guiding principle underlying the welfare assessments is a primary focus on the measurement of affective experiences. Aspects such as health, function and natural living are only important in this framework to the extent that they influence the subjective affective experiences of individuals. For example, subclinical health conditions, growth impairment or physical disabilities not associated with any type of unpleasantness (physical or psychological) in the short- or long-run are not considered relevant. Nor is the loss or deprivation of resources, or natural behaviors, that are not missed or valued by the animal (Dawkins, 2023). Affective experiences are taken as what matters to welfare.

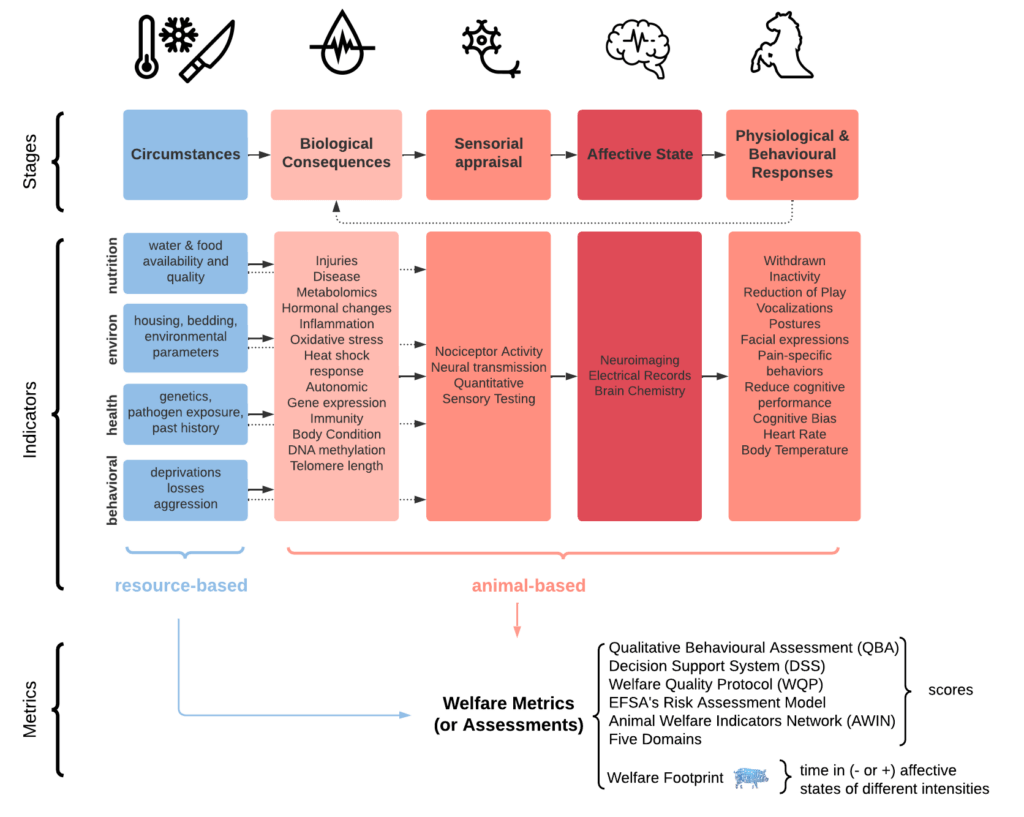

Welfare indicators: discernable traits and signals that, based on evidence, are deemed to be correlated to a greater or lesser extent with an individual’s affective state. Indicators are often specific to a species or group of animals. They can include neurological, physiological, behavioral, environmental, pharmacological, immune and anatomical factors. Welfare indicators are typically characterized as resource-based, such as environmental factors like food and water availability, temperature, and space available, and animal-based, which include, among others, spontaneously occurring behaviors specific to pain, changes in activity, social interaction patterns, attention and cognitive performance, vocalizations, facial expressions, neuroendocrine hormones, and autonomic responses (see more here).

Welfare metrics: quantitative constructs used to evaluate and compare animal welfare across different situations or over time. They are informed by welfare indicators and are often combined to create composite scores or indices that provide a more comprehensive assessment of animal welfare. Unlike welfare indicators, welfare metrics should be as universal and comparable as possible. Welfare metrics can be used to assess animal welfare in the field, inform decisions, or track progress. Examples of welfare metrics include the Cumulative Pain, the welfare risk scores developed by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and in semantic models such as COWEL and SOWEL. Metrics used in assessments of animal welfare at the farm level include the scoring system of the Welfare Quality Protocol, AWIN Protocol and Animal Needs Index (see more here).

This figure illustrates the animal welfare assessment process, from initial hazardous Circumstances through to the observable coping responses of organisms (e.g., behavioral and physiological indicators of pain). It categorizes indicators and links them to specific stages of the process leading to affective experiences. ‘Resource-based’ (upstream) indicators, represented by a tree symbol, correspond to four of the Five Domains. Numerous additional indicators are associated with different stages of the response process (with the mental state domain linked to the ‘Affective State (Pain)’ box). These indicators are essential for informing metrics and frameworks used in animal welfare assessments.

A comprehensive analytical module (Module I) designed to organize and map information about the welfare conditions of sentient organisms. It structures the living environment into five hierarchical levels—Species, Production System, Life-Fates, Life-Phases, and Circumstances—while simultaneously defining the Species-Specific Needs to evaluate downstream biological consequences, and recording baseline Productivity metrics (e.g., yield per animal) to enable the standardization of welfare footprints.

[Species]: The sentient species under examination or care.

[System] and [Production System]: The conditions in which the population of interest lives, encompassing everything from farming systems (e.g., intensive, semi-intensive, extensive), environments like zoos and sanctuaries, laboratory settings, natural habitats (wild animals) to socio-economic environments (in the case of humans).

[Life-Fate]: The roles or destinies of individuals within a species, characterized by the commonalities in critical life events and hazards they face (Alonso and Schuck-Paim 2017). For example, in a pig production system, different life-fates could include: (1) breeding females (sows): female pigs kept for reproductive purposes, (2) Market pigs: raised primarily for meat, (3) male breeders: male pigs kept for breeding purposes.

[Life-Phases]: The major life stages of a Life-Fate of interest, each presenting unique challenges and welfare implications. For example, in the case female breeding pigs, the following phases are present: (1) Suckling, (2) Postweaning, (3) Growth, (4) Pre-puberty, (5) Breeding Cycle: repetitive cycle involving conception, gestation, and farrowing, (6) Transportation, (7) Slaughter.

[Circumstance]: refers to the internal and external conditions—physical, social, environmental, genetic, and procedural—that shape the lives of animals during each Life-Phase. These include housing dimensions, resource availability, social configurations, management practices, and inherited traits such as breed or genotype. Crucially, Circumstances do not directly cause affective experiences, but do so through the Biological Consequences they generate. Examples of Circumstances include housing design, group size, lighting schedules, enrichment access, feeding regimes, handling methods, or genetic predispositions. These are described for each Life-Phase of every Life-Fate, as their combination sets the stage for how an animal’s biology responds to its environment.

Biological Consequences: are the physiological, anatomical, neurological, or cognitive changes that result from an organism’s exposure to internal or external Circumstances, or from its own Affective Experiences. These consequences include not only physical manifestations (e.g., wounds, inflammation, metabolic imbalances), but also sensorial and perceptual states (e.g., detecting a threat, perceiving novelty, or recognizing a conspecific) that act as the proximate precursors of affective responses. Conversely, Affective Experiences—particularly when intense or prolonged—can generate or modulate Biological Consequences. For instance, chronic fear or stress may alter hormonal profiles, immune function, or behavior, creating a feedback loop between emotional states and biological condition.

Negative Physical Consequences: Detrimental changes to the animal’s body or physiological state that arise from adverse circumstances or internal imbalances, leading to negative affective states such as pain, discomfort, or fatigue.

Negative Perceptual Consequences: Blocking of psychological motivations (an animal is strongly driven to perform a behavior but is prevented from doing so), or changes in the animal’s perceptual state that elicit negative affect (e.g., perception of threat, social instability) without necessarily involving physical harm.

Positive Physical Consequences: Fullfilment of motivations for physical needs, or changes in the animal’s physical state, that result in positive affective states (e.g., eating, drinking, copulation).

Positive Perceptual Consequences: Fullfiment of motivations for psychological needs (e.g., expression of behaviors), or changes in the animal’s perceptual state without necessarily arising from a pre-existing drive (e.g., spontaneous play, novel sensory or social stimuli) that elicit pleasure.

Pathways are particular progressions through which a Biological Consequences unfolds in different groups of animals, leading to different types of Affective Experience. Common pathways include: Acute vs. Chronic, Fatal vs. Non-fatal.

Scale of the Biological Consequences, defined based on clinical or observable criteria (e.g., wound depth, disease stage, gait score). For example, a superficial scratch is less severe than a deep, infected wound. The distinction matters because different severities produce different intensities and durations of affective experience.

The extent to which a behavioral or physiological motivation is thwarted. For example, a hen with no access to a nest may experience intense frustration, while one with a less preferred nest may experience a lower level of frustration. These are different affective experiences and must be disaggregated accordingly when possible.

The extent a behavioral or physiological motivation is satisfied. For instance, the intensity of pleasure a hen pecking inert litter may experience is likely different than one foraging in a rich, rewarding substrate.

General Affective Experiences & States:

Affective Experience: The complete, dynamic emotional event or episode resulting from specific Biological Consequences. Affective experiences can be positive or negative. In the Welfare Footprint Framework, they are the overarching phenomena being evaluated and are referred to, generally, as ‘Pain from …’ and ‘Pleasure from …’, respectively.

Affective State: The specific condition or level of intensity an animal occupies at a given point in time during an Affective Experience (e.g., Annoying, Hurtful, Joy, Euphoria).

Negative Affect (Pain):

Pain (Operational Definition): Broadly defined as any felt negative affective state. This includes both [physical pain], namely states with a somatic origin (e.g. aches, hunger, injuries, thermal stress) that are often the consequence of [Negative Physical Consequences], and [psychological pain], states related to the primary emotional systems (e.g. fear, frustration, boredom) that are often the consequence of [Negative Perceptual Consequences].

Pain (Proposal for a New Definition): Pain is a conscious experience, evolved to elicit corrective behavior in response to actual or imminent damage to an organism’s survival and/or reproduction. Still, some manifestations, such as neuropathic pain, can be maladaptive. It is affectively and cognitively processed as an adverse and dynamic sensation that can vary in intensity, duration, texture, spatial specificity, and anatomical location. Pain is characterized as ‘physical’ when primarily triggered by pain receptors and as ‘psychological’ when triggered by memory and primary emotional systems. Depending on its intensity and duration, pain can override other adaptive instincts and motivational drives and lead to severe suffering.

Cumulative Pain: The total estimated time an individual or population spends in negative affective states of varying intensities (Annoying, Hurtful, Disabling, Excruciating). Rather than aggregating these experiences into a single weighted score, Cumulative Pain is maintained as a disaggregated metric, calculated by summing the time spent strictly within each distinct intensity category. The metric is modular and can be computed at different analytical levels, ranging from a single negative Affective Experience to the entire lifespan of a population, or standardized per unit of product. To ensure transparency and interpretability, it should always be presented with an explicit scope qualifier (e.g., Cumulative Pain [Episode], Cumulative Pain [Lifespan], Cumulative Pain [per kg])

Pain-Track: A notation method for describing negative affective experiences based on their temporal evolution. It considers both the intensity and duration of pain for each phase of a pain episode, allowing for the integration of available scientific evidence .

Pain Intensity: Intensity, when referred to in relation to pain, denotes the subjective measure of unpleasantness or aversiveness experienced by an individual. This measure is not directly tied to the physical stimuli’s magnitude but rather to the personal, subjective experience of the pain’s severity or distress.

Definition of Pain Intensity Categories: click here.

Positive Affect (Pleasure):

Pleasure (WFF Operational Definition): any felt positive affective state.

Pleasure (extended WFF Definition): Pleasure is a conscious experience, evolved to elicit or reinforce behaviors beneficial to an organism’s survival and/or reproduction. It is affectively and cognitively processed as a positive and dynamic sensation that can vary in intensity, duration, texture, spatial specificity, and anatomical location. Pleasure is characterized as ‘physical’ when primarily triggered by stimuli that are directly rewarding or enjoyable, and as ‘psychological’ when triggered by cognitive processes, memories, and emotional states. Depending on its intensity and duration, pleasure can override other adaptive instincts and motivational drives, leading to states of dependency and self-damage.

Cumulative Pleasure: The total estimated time an individual or population spends in positive affective states of varying intensities (Satisfaction, Joy, Euphoria, Bliss). Rather than aggregating these experiences into a single weighted score, Cumulative Pleasure is maintained as a disaggregated metric, calculated by summing the time spent strictly within each distinct intensity category. The metric is modular and can be computed at different analytical levels, ranging from a single positive Affective Experience to the entire lifespan of a population, or standardized per unit of product. To ensure transparency and interpretability, it should always be presented with an explicit scope qualifier (e.g., Cumulative Pleasure [Episode], Cumulative Pleasure [Lifespan], Cumulative Pleasure [per liter]).

Pleasure-Track: a notation method for describing the positive affective experiences based on their temporal evolution. It considers both the intensity and duration of pleasure for each phase of a pleasure episode, allowing for the integration of available scientific evidence.

Pleasure Intensity: Intensity, when referred to in relation to pleasure, denotes the subjective measure of pleasantness experienced by an individual. This measure is not directly tied to the stimuli’s magnitude but rather to the personal, subjective experience.

Definition of Pleasure Intensity Categories: click here

Average Population Member. An analytical construct used to estimate the per-capita welfare burden of a Target Population. Because individuals within a population experience different hazards (e.g., a large fraction of broilers may experience lameness, but only a few experience fatal ascites), the WFF distributes the total population burden equally to determine the expected time in each affective intensity for a representative individual. This is calculated by multiplying the Cumulative Affect of an episode by the frequency of the Affective Experience and the prevalence of the underlying Biological Consequence. The final results must be expressed with an explicit Scope Qualifier (e.g., Cumulative Pain [Lifespan]).

Target Population: A specific group of animals defined by shared characteristics, environments, and living conditions that form the boundary of the risk assessment. (EFSA, 2012).

[Freedom Evaluation Questions]: specific questions designed to evaluate the circumstances in which organisms live that impact their welfare. These questions are structured around the Five Freedoms [6] framework and address various circumstances, such as environmental conditions, social needs, and health care.

[Specific Freedom]: One component of the Five Freedoms framework for animal welfare [6], which includes freedom from hunger and thirst; discomfort; pain, injury, or disease; to express normal behavior; and from fear and distress. Each freedom addresses one fundamental aspect of animal well-being.

[Life Interval of Interest, in days]: The number of days under consideration for a specific analysis. This can either encompass the entire lifespan of an organism or a designated period of interest, such as a specific life-phase. This interval is set based on the study’s scope or the data’s availability.

[Total Hours in Pain in Life Interval of Interest]: The cumulative number of hours an organism spends in pain during the ‘Life Interval’. This is calculated by multiplying the days during which a Biological Consequence persists within the interval by the number of hours of pain experienced on each of those days.

[Days that the Condition Lasts in Life Interval of Interest]: The total number of days within the ‘Life Interval’ during which the organism experiences a specific Biological Consequence that causes pain.

[Hours in Pain (or Pleasure) within Days with the Consequences]: The average number of hours per day an organism experiences pain when the Biological Consequences is active. This measure accounts for the variability in the duration of pain across different days.

[Proportion of Life Interval of Interest in Pain]: The fraction of the ‘Focused Life Interval’ during which the organism is in pain, expressed as a percentage. This is calculated by dividing the ‘Total Hours in Pain in the Life Interval’ by the total hours in the entire ‘Life Interval’ (which is the product of the number of days in the interval and 24 hours per day).

Definition of Uncertainty Intervals: click here