Defining Affective Experiences

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Wladimir J. Alonso & Cynthia Schuck-Paim

It may initially appear that discussions around the concepts of welfare metrics and welfare indicators are abstract and perhaps without tangible benefits. Yet, the truth is, some degree of precision in terminology is required when it comes to assessments of animal welfare. Welfare metrics and welfare indicators are terms often used interchangeably, but they are not equivalent.

Welfare indicators are empirical measurements of specific traits or states that, based on evidence, are deemed to be correlated to a greater or lesser extent with an individual’s affective state. These indicators are a set of measures typically specific to a species and context of measurement. They can include neurological, physiological, behavioral, environmental, pharmacological, immune, and anatomical factors. Welfare indicators are typically characterized as resource-based, such as environmental factors like food and water availability, temperature, and space available, and animal-based, which include, among others, spontaneously occurring behaviors specific to pain, changes in activity, social interaction patterns, attention and cognitive performance, vocalizations, facial expressions, neuroendocrine hormones, and autonomic responses. Indicators typically offer only a partial picture of welfare.

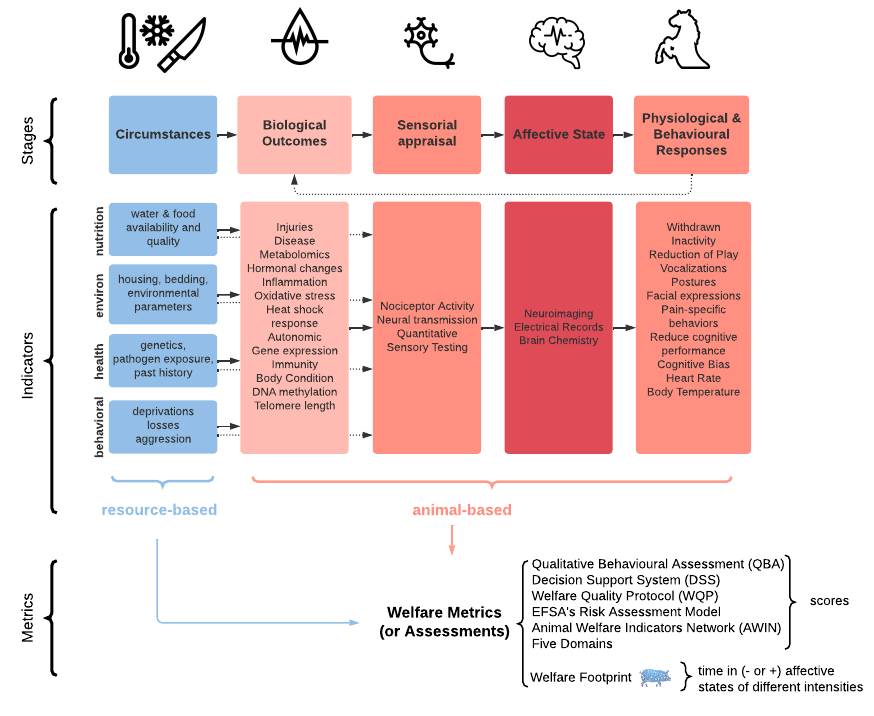

In general, the closer a trait is to the biological processes leading to the emergence of an affective experience, the greater the validity of this trait as an indicator of welfare. For instance, if an animal is in a housing system where the number of drinkers is clearly insufficient, one could reasonably suspect that this animal will experience thirst at some point. While useful, this is an indirect (“resource-based”) measure of welfare that does not reliably correlate with affective experiences, the ultimate target of assessment. Animal-based indicators are therefore more reliable welfare indicators, as they are typically the direct outcome of the processes that lead to the emergence of ‘Affective States’ (see diagram below). For example, the responses to a number of biological challenges (‘Negative Conditions’), as measured by anatomical, neurophysiological, and immunological parameters (e.g., inflammation, immune responses, hormone levels, oxidative stress, gene expression) can often indicate the level of disturbance endured by an organism, though the degree to which these markers are associated with affect is not always clearly established. Indicators of neural activity (‘Sensory Appraisal’), in turn, indicate the neuronal activity that carries pain signals to the brain and can therefore be quite informative. However, the most accurate and specific representation of the affective experience of interest would be the one collected directly from the brain, as a direct result of the ‘Affective State’ at each moment (e.g., neural signatures of pain or pleasure would be powerful indicators once the technology becomes available, as they would directly reflect the origin of these affective states). Finally, the responses triggered by specific affects (vocalizations, posture, preferences, expressions, changes in activity levels) are particularly valuable for being the direct outcome of the affective experiences endured. In fact, there is one welfare metric, the Qualitative Behavioural Assessment, that is based solely on behavioral indicators.

Diagram to help organize Welfare Indicators and Metrics. This diagram is based on negative affective states (operationally referred to as pain), but the same logic can be applied to positive experiences. The first row presents a simplified sequence of the stages involved in negative affective states, from the initial Circumstances (blue boxes) to the behavioral and physiological responses of organisms. Below each stage, we have the indicators that can be detected at each stage. ‘Resource-based’ (upstream, within blue boxes) indicators and ‘animal-based’ indicators (downstream, within orange-red boxes) are essential for informing various metrics and frameworks used in animal welfare assessments. These metrics are divided between those that are score-based and those that are non-score-based, with the Welfare Footprint being the only representative of the latter category (figure modified from Alonso & Schuck-Paim ‘The Comparative Measurement of Animal Welfare: the Cumulative Pain Framework‘).

Welfare metrics, in turn, are quantitative constructs used to evaluate and compare animal welfare across different situations or over time. They are informed by welfare indicators and are often combined to create composite scores or indices that provide a more comprehensive assessment of animal welfare. Unlike welfare indicators, welfare metrics should be as universal and comparable as possible and should ideally be easily interpretable by a wide audience and across disciplines.

Welfare metrics can be used to assess animal welfare in the field, inform decisions, or track progress. Examples of welfare metrics include the welfare risk scores developed by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and in semantic models such as COWEL and SOWEL. Metrics used in assessments of animal welfare at the farm level include the scoring system of the Welfare Quality Protocol, AWIN Protocol and Animal Needs Index. Finally the the Welfare Footprint, is a metric that, different from the previous ones, measures time spent in various affective states of different intensities rather than providing a single composite score.

The distinctions between welfare metrics and welfare indicators are summarized in the table below.

Table 1. Conceptual differences between welfare metrics and welfare indicators.

Welfare Indicators | Welfare Metrics | |

Measurement | Typically empirical measurements of specific traits or states | Constructs based on integration of information provided by welfare indicators |

Standardization (units of measurement) | Each indicator is measured with different methods, in different units and time frames depending on the species | Ideally, consensus should be reached for adoption of a single welfare metric, facilitating integration of efforts and communication* |

Applicability | Typically specific to a context and species | Ideally applicable across contexts and even species |

Scope | Indicators can be correlated to different degrees with well-being, in time frames typically limited by the nature of the indicator | Integration of subjective experiences (affective states) over entire time horizon of interest |

Interpretability | Welfare indicators often require in-depth knowledge of the species and nature of the indicator | Should be easily interpretable by a wide audience and across disciplines. |

Examples | Behavior, neurophysiology, clinical signs, anatomy, immune function, preferences | Welfare Footprint, Welfare Quality Scores, EFSA Scores, Semantic scores |

*Standardization between species based on their capacity for welfare is still required

In summary, while welfare indicators provide specific empirical measurements of traits or states, welfare metrics are constructs based on the integration of information provided by these indicators. They are designed to be universally applicable and easily interpretable by a wide audience across disciplines, facilitating the assessment and comparison of animal welfare in various contexts and over time.

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Confounding Factors in Welfare Comparisons of Animal Production Systems Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable

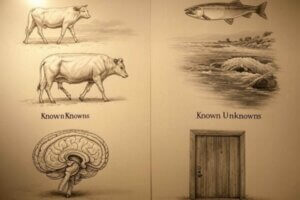

Borrowing the Knowns and Unknowns Framework to Reveal Blind Spots in Animal Welfare Science Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim There is always a risk of fixating on what we already