Defining Affective Experiences

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim

Center for Welfare Metrics, Brazil

To inform efforts for the prevention and alleviation of animal suffering, the Welfare Footprint Project has so far primarily focused on quantifying negative affective experiences [1], often referred to simply as ‘pain.’ This emphasis is based on the understanding that negative experiences generally have a greater impact on well-being than positive ones, often preventing the experience of positive states [2]. From an evolutionary standpoint, pain is expected to be more noticeable than pleasure, as pain signals immediate threats to survival and reproduction, whereas positive experiences tend to reinforce behaviors that are beneficial in the medium term, like social bonding, learning, optimal foraging and mating. Failing to experience pleasure is not as immediately consequential as not responding to pain. This tendency to focus more on negative than positive events, known as negativity bias, is in fact a well-documented phenomenon in humans [3].

Still, positive states also play a crucial role in shaping an individual’s quality of life, and determining the extent to which it is ‘good’ [4], or at least ‘worth living’ [5]. Positive states are not only momentarily pleasurable; they also have long-term effects that help individuals overcome adversity [6]. For example, experiences of positive affect have been shown to naturally relieve pain (through endogenous analgesia), boost resilience to stress, and improve immune function [7–9]. Accordingly, the assessment of positive affect and the identification of conditions promoting it have gained substantial traction in the animal welfare sciences in recent years [10–12].

The goal of this contribution is to expand the Welfare Footprint framework to include not only the measurement of negative experiences in animals, but also positive states, or ‘pleasure’. Since the reasoning behind this metric is similar to that for assessing pain — already discussed in prior works [1,13] (see a 8 min video or a presentation at the Effective Altruism conference) — we do not describe these principles again here. Instead, we introduce the definitions and tools equivalent to those used for the quantification of negative affective states, now adapted for positive affect: the operational definitions of ‘pleasure’ and its four different intensity levels, the ‘Pleasure-Track’ notation system, and the ‘Cumulative Pleasure’. Additionally, with the full spectrum of affective experiences considered, we also introduce a visualization proposal, termed ‘Cumulative Affect’, to represent the overall Welfare Footprint of any population in a context and time scope of interest.

We propose an operational definition of pleasure directly derived from the operational definition of pain previously proposed [14], as follows:

“Pleasure is a conscious experience, evolved to elicit or reinforce behaviors beneficial to an organism’s survival and/or reproduction. It is affectively and cognitively processed as a positive and dynamic sensation that can vary in intensity, duration, texture, spatial specificity, and anatomical location. Pleasure is characterized as ‘physical’ when primarily triggered by stimuli that are directly rewarding or enjoyable, and as ‘psychological’ when triggered by cognitive processes, memories, and emotional states. Depending on its intensity and duration, pleasure can override other adaptive instincts and motivational drives, leading to states of dependency and self-damage.”

In the Welfare Footprint Framework, pain intensity categories are operationally defined based on the assumption that more unpleasant sensations should be more disruptive, engaging a greater share of attention. [15,16]. This is rooted in the evolutionary expectation that the greater the threat, the more intense the signal should be to ensure it is prioritized over other functions and behaviors [17,18]. A similar approach can be used to define categories of pleasure intensity, with intensity categories defined based on the degree of engagement with positive experiences. First, the degree of engagement in experiences is likely to correspond to the hedonic value of these experiences [6]. A greater motivation to play, interact socially and explore is likely driven by a more intense positive experience. Second, the degree of motivation to engage in positive experiences is also likely to match their broader adaptive value [19]. Just as pain intensity often signals threat severity, pleasure intensity may correlate with the evolutionary importance of the activity, such as resource holding, learning, parental care, and mating (though maladaptive exceptions can be present, such as addiction in humans and feather-plucking in birds).

Similarly with the case of pain, here we propose the use of emphatic and universally recognized terms, focusing on concepts that reflect the degree of engagement with the pleasurable state. The definitions of pain intensities were first presented in a paper aimed at the medical audience [13], but designed to maintain their universality for non-human animals. This same broad approach is used to define pleasure intensities:

Just as we recently included the category ‘no pain’ as an additional intensity level (zero pain), it is also convenient, whenever relevant, to include the category ‘no pleasure,’ which represents the hypothesis that no positive affective states are experienced over the period of interest.

The Pleasure-Track is a notation system analogous to the Pain-Track [13], where hypotheses on the temporal evolution and intensity of positive affective states are described. To this end, each experience is atomized into a level of analysis that is justifiable through empirical evidence. This is done by decomposing each experience into meaningful time segments, where each time segment is characterized by an expected intensity. Next, hypotheses about the intensity and duration of the experience at each of these segments can be informed by empirical evidence.

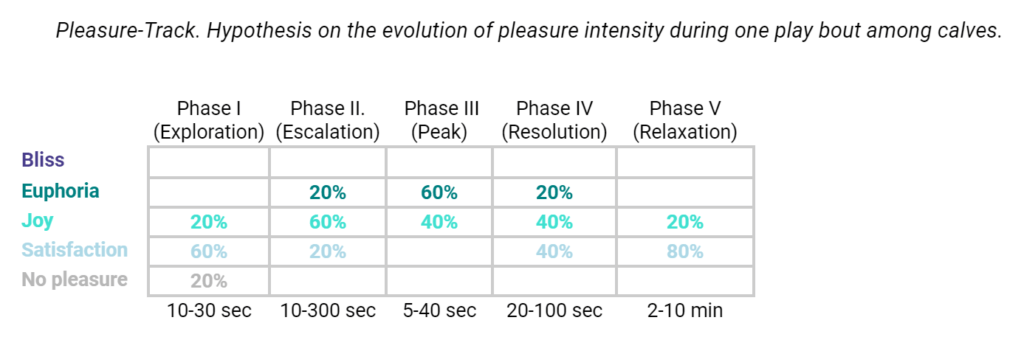

To illustrate the concept of a Pleasure-Track, we consider the hypothetical intensity and duration of play bouts in young calves, as follows: (Phase I) the play session begins with calves engaging in light play or exploration. This includes behaviors such as gently nudging or sniffing play objects, or light social interactions with other calves. The engagement is present but not overwhelming, allowing the calves to remain aware of their surroundings and easily shift their focus to other stimuli. As the play behavior escalates (Phase II), calves enter a state characterized by more vigorous activities such as running, jumping, and robust social play like head-butting or chasing. The calves show a clear focus on these rewarding activities, with their behavior directed towards maintaining or enhancing the experience. Physiological indicators might include increased heart rate or more expressive body language, reflecting their engagement in the play. The peak of the play experience (Phase III) is where the activity becomes the primary focus of the calves’ attention, with calves fully immersed in play, displaying spontaneous expressions of pleasure such as vocalizations or exuberant body movements. After reaching the peak of excitement, the intensity of play begins to decrease. Calves may start to engage in less vigorous activities, such as slower running or gentle nudging, as they start to wind down from the high energy play. This stage (Phase IV) is characterized by a gradual reduction in the intensity of their actions and a shift towards more relaxed behaviors. When the play bout concludes (Phase V) calves often display behaviors indicative of relaxation. This may include lying down, social grooming, or simply resting in close proximity to their playmates. The Pleasure-Track below summarizes these hypothetical ethological observations for a group of calves. Average phase durations are also hypothetical, and in real scenarios are expected to vary with factors such as the species, age, space available, group size, climatic conditions, time of day, and hunger [20].

As with the Pain-Track, the Pleasure-Track is designed to capture situations in which there is uncertainty in the classification of the intensity of pleasure. Therefore, probabilities are used to represent how likely it is that each category of pleasure intensity is experienced. Uncertainty (or natural variation) regarding how long each phase of the experience lasts is captured in the range of values at the bottom row of each temporal segment. The Pleasure-Track illustrated above is hypothetical, but in real situations, each numerical input should be based on a thorough review of evidence from various sources. Because evidence will be often limited, criticism of the proposed values should be always encouraged.

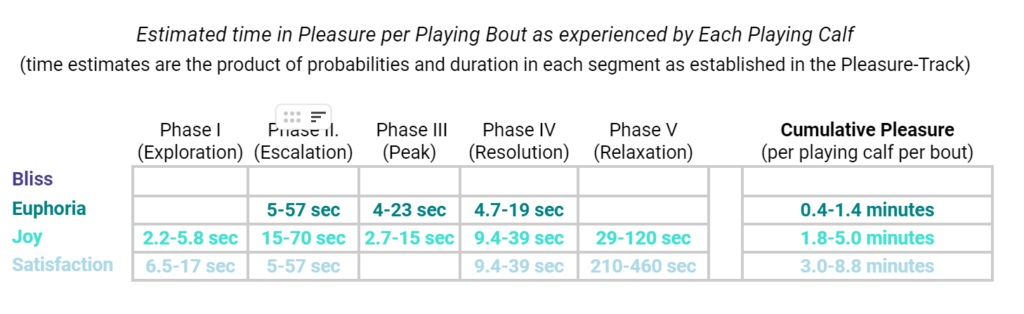

Like with estimates of cumulative time in negative states (‘Cumulative Pain’), it is also possible to estimate ‘Cumulative Pleasure’, namely the time spent in positive affective states of different intensities, as follows:

The assessment of Cumulative Pleasure for an individual over a certain period or even their lifetime, can be also established by determining the cumulative impact of all the positive events experienced. Similar to negative experiences, this is best represented as the sum of the time spent in positive states from all these events, whether they happen sequentially or simultaneously. This also includes events that happen repeatedly. For instance, if young calves play as described in the hypothetical scenario 1-8 times a day for 4 weeks, the Cumulative Pleasure for each calf would be a total of approximately 15-130 minutes of Euphoria, 1 to 7.3 hours of Joy, and 1.7 to 13.3 hours of Satisfaction. This is the of the estimates shown in the Pleasure-Track, daily frequency of playing bout and total number of days playing.

Of course, different positive experiences can interact with each other in various ways, both physically and psychologically. These effects, when potentially leading to changes in the outcomes, must be investigated on a case-by-case basis.

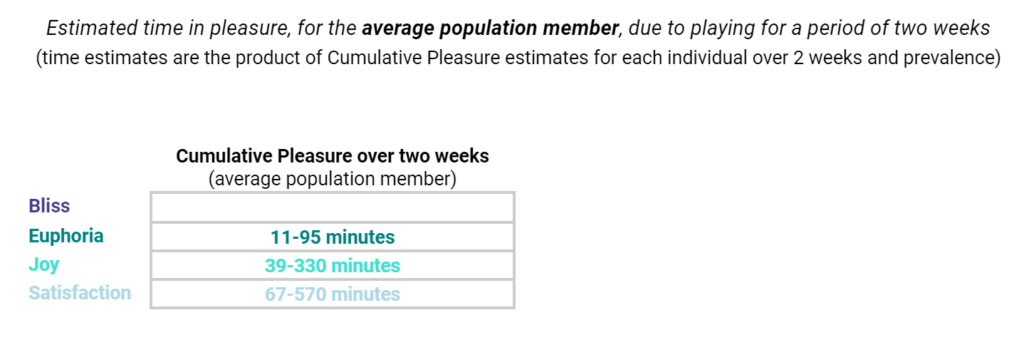

Cumulative Pleasure can be also calculated at the population level. This requires accounting for differences in the exposure of population members to different positive experiences. This is achieved by weighting estimates by the prevalence of each experience, which enables determining the cumulative time in pleasure experienced by an average member of the population. For example, in the hypothetical scenario of play in calves, Cumulative Pleasure could be weighted by the proportion of the calf population playing in the period of interest. For instance, if 50-90% of the calves played over the period of two weeks, Cumulative Pleasure for the average population member over this period would be the product of this prevalence and Cumulative Pleasure for each individual over the two weeks (resulting in 15-130 minutes of Euphoria, 59-440 minutes of Joy and 100-800 minutes of satisfaction)

As with estimates of time spent in pain, we don’t combine the four categories of pleasure intensity into a single one. This is because, as thoroughly discussed for pain [21], there are no empirical references to establish a weighting system between the intensity categories, hence a single scale of pleasure.

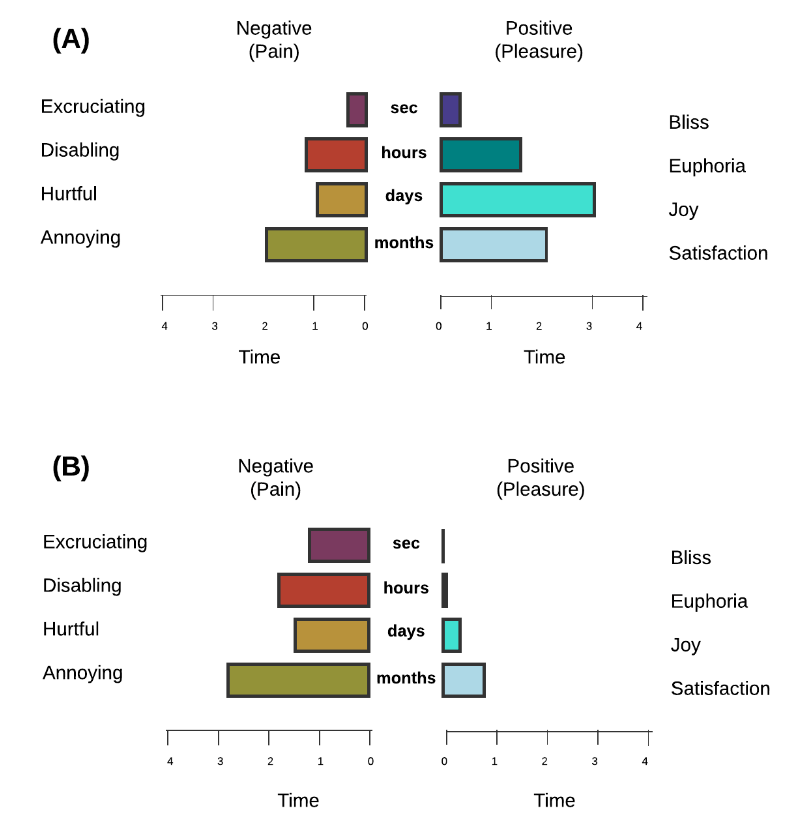

By considering positive experiences, Welfare Footprints can be expressed as the time spent in negative and positive affective states of different intensities, i.e., Cumulative Pain and Cumulative Pleasure. To help visualize these effects, we propose to present Welfare Footprints as a double bar chart, as illustrated in the examples below. This graphical representation juxtaposes the time spent in negative affective states against the time spent in positive affective states, across various intensities. The figure illustrates two footprints, depicting the distribution of time spent by an individual (or population, if the prevalence of different pains and pleasures are factored in the analysis) at each intensity of pain and pleasure (note that the quality of life depicted in the first Welfare Footprint [A] is clearly better than in the second [B]):

The time units used in the chart for each intensity category (seconds, hours, days, and months) are flexible and can be adjusted. However, because of this flexibility, it is crucial to always specify the units in the chart.

Because positive and negative intensities are displayed side by side, it is important to reiterate that no equivalence is implied. For instance, whether 10 seconds on the most intense form of pleasure (‘Bliss’) can be considered a direct counterpart of 10 seconds under the most intense form of pain (‘Excruciating’) remains to be determined.

The welfare of sentient organisms is shaped by a complex interplay of positive and negative affective states [6,19,22]. While combining both positive and negative experiences would offer a fuller picture of their affective lives, there are many challenges to measure or compare these states ethically or quantitatively [5,23–27]. For example, Shriver [26] challenges the idea that pleasure and pain are just two ends of a continuum, pointing out that these states are driven by different cognitive processes, contribute differently to overall well-being, and have separate relationships with motivational systems. Considering these complexities, we do not attempt estimating how cumulative time in pain and pleasure might balance each other out. Instead, we focus on describing and measuring these affective states in a transparent and relatable way: by estimating time spent in states of pleasure and pain, at different levels of intensity.

We still maintain that negative states have a disproportionate impact on an individual’s life and welfare. Pain, especially when severe, can prevent the possibility of positive experiences. However, positive experiences and states are valuable, especially when more intense sources of pain have already been mitigated. Therefore, Welfare Footprints must not overlook this aspect. This text is aimed at incorporating positive experiences into the Welfare Footprint framework. Welfare Footprints that focus solely on pain are already valuable (especially for addressing the extreme situations many captive animals face), but a more comprehensive approach that includes positive experiences can provide a richer assessment. This complete version of a Welfare Footprint can thus better guide animal welfare policies, inform advocacy groups, and enhance public awareness about the ethical implications of animal use.

1. Alonso WJ, Schuck-Paim C. The Comparative Measurement of Animal Welfare: the Cumulative Pain Framework. In: Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ, editors. Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens. Independently published. https://tinyurl.com/bookhens; 2021.

2. Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ. How attention modulates the perceived intensity and duration of simultaneous affective experiences:Implications for refining Cumulative Pain estimates and for determining the potential for positive welfare. In: Welfare Footprint Project [Internet]. 16 Apr 2023 [cited 5 May 2023]. Available: https://welfarefootprint.org/2023/04/16/method-refinement-attention/

3. Norris CJ. The negativity bias, revisited: Evidence from neuroscience measures and an individual differences approach. Soc Neurosci. 2021;16: 68–82.

4. Rowe E, Mullan S. Advancing a “Good Life” for Farm Animals: Development of Resource Tier Frameworks for On-Farm Assessment of Positive Welfare for Beef Cattle, Broiler Chicken and Pigs. Animals. 2022;12: 565.

5. Yeates J. Better to have lived and lost – the concept of a life worth living. In: Butterworth A, editor. Animal Welfare in a Changing World. CAB International; 2018. pp. 162–170.

6. Leknes S, Tracey I. A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9: 314–320.

7. Yeates JW, Main DCJ. Assessment of positive welfare: a review. Vet J. 2008;175: 293–300.

8. Moskowitz JT, Saslow LR. Health and psychology: The importance of positive affect. In: Tugade MM, editor. Handbook of positive emotions (pp. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press, xv; 2014. pp. 413–431.

9. Gentle MJ. Attentional Shifts Alter Pain Perception in the Chicken. Anim Welf. 2001;10: 187–194.

10. EU. Action project to provide the background for including positive welfare in farm animal welfare assessment. In: LIFT – COST ACTION [Internet]. Super Admin; 2022-2026 [cited 28 Feb 2024]. Available: https://liftanimalwelfare.eu/

11. Mellor DJ. Animal emotions, behaviour and the promotion of positive welfare states. N Z Vet J. 2012;60: 1–8.

12. Mellor DJ. Updating Animal Welfare Thinking: Moving beyond the “Five Freedoms” towards “A Life Worth Living.” Animals (Basel). 2016;6. doi:10.3390/ani6030021

13. Alonso WJ, Schuck-Paim C. Pain-Track: a time-series approach for the description and analysis of the burden of pain. BMC Res Notes. 2021;14: 229.

14. Alonso WJ, Schuck-Paim C. A Novel Proposal for the Definition of Pain. pre-print (OSF). 2023; 2.

15. Barclay RJ, Herbert WJ, Poole T. The disturbance index : a behavioural method of assessing the severity of common laboratory procedures on rodents. UFAW, Universities Federation for Animal Welfare; 1988.

16. Eccleston C, Crombez G. Pain demands attention: a cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychol Bull. 1999;125: 356–366.

17. Merker B. Drawing the line on pain. Animal Sentience: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Animal Feeling. 2016;1: 23.

18. Mellor DJ, Beausoleil NJ, Littlewood KE, McLean AN, McGreevy PD, Jones B, et al. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals (Basel). 2020;10. doi:10.3390/ani10101870

19. Mellor DJ. Positive animal welfare states and encouraging environment-focused and animal-to-animal interactive behaviours. N Z Vet J. 2015;63: 9–16.

20. Whalin L, Weary DM, von Keyserlingk MAG. Understanding Behavioural Development of Calves in Natural Settings to Inform Calf Management. Animals (Basel). 2021;11. doi:10.3390/ani11082446

21. Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ, Hamilton C. Short agony or long ache: comparing sources of suffering that differ in duration and intensity. Effective Altruism Forum. 2024. Available: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/editPost?postId=C2qiY9hwH3Xuirce3)

22. Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML. Neuroscience of affect: brain mechanisms of pleasure and displeasure. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23: 294–303.

23. Reimert I, Webb LE, van Marwijk MA, Bolhuis JE. Review: Towards an integrated concept of animal welfare. Animal. 2023;17 Suppl 4: 100838.

24. Poirier C, Bateson M, Gualtieri F, Armstrong EA, Laws GC, Boswell T, et al. Validation of hippocampal biomarkers of cumulative affective experience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;101: 113–121.

25. Suffering and happiness: Morally symmetric or orthogonal? In: Center for Reducing Suffering [Internet]. 9 Sep 2020 [cited 29 Feb 2024]. Available: https://centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/suffering-and-happiness-morally-symmetric-or-orthogonal/

26. Shriver A. The Asymmetrical Contributions of Pleasure and Pain to Subjective Well-Being. RevPhilPsych. 2014;5: 135–153.

27. Tomasik B. Are Happiness and Suffering Symmetric? [cited 29 Feb 2024]. Available: https://reducing-suffering.org/happiness-suffering-symmetric/

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Confounding Factors in Welfare Comparisons of Animal Production Systems Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable

Borrowing the Knowns and Unknowns Framework to Reveal Blind Spots in Animal Welfare Science Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim There is always a risk of fixating on what we already