The industrialization of salmon aquaculture mirrors concerning patterns seen in terrestrial animal farming, particularly poultry production. As the industry intensifies through selective breeding, accelerated growth protocols, and high-density production systems, multiple welfare challenges have emerged that affect millions of animals annually.

Atlantic salmon represent a critical case study in aquaculture welfare for several reasons:

Strong Evidence Base: Salmonids are among the best-studied farmed fish species regarding welfare, behavior, and physiological pain markers, providing robust data for assessment.

Significant Scale: With two-year production cycles and high mortality rates, the welfare footprint is substantial. The industry’s heavy reliance on antibiotics, fishmeal, and cleaner fish further amplifies its impact.

Growing Global Impact: Salmon farming continues to expand, particularly in emerging markets, making it the largest single fish commodity by value since 2013.

The welfare of farmed Atlantic salmon during their marine grow-out phase has received considerable attention, yet the long-term implications of juvenile rearing conditions remain poorly understood. The incentives for year-round production, increased productivity and biosecurity has led to fundamental changes in how juvenile salmon are produced, with most commercial operations now raising smolts in intensive land-based Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS).

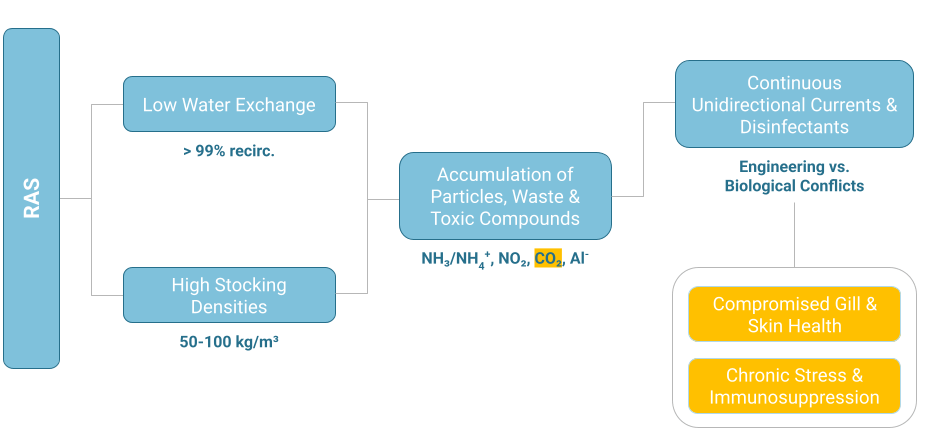

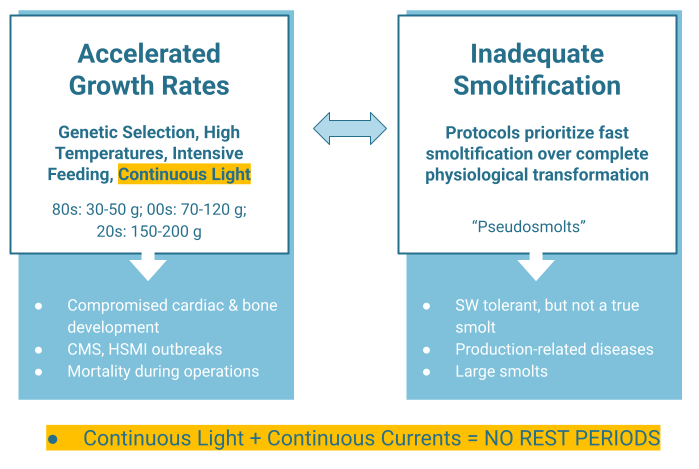

The Welfare Footprint team working on salmon welfare, led by Patricia Pereira, has conducted a comprehensive review examining how intensification of the hatchery phase impacts salmon welfare across their life cycle. Our study reveals that economic constraints of RAS creates major conflicts between production requirements and biological needs. For example, minimum stocking densities required for economic viability not only prevent natural behaviors but create compounding water quality challenges. The combination of high densities and limited water exchange characteristic of RAS leads to rapid accumulation of metabolic wastes, CO₂, and suspended solids, increasing the likelihood of toxicity. Chronic stress from suboptimal environmental conditions is exacerbated by accelerated growth rates—achieved through genetic selection, high temperatures, continuous lighting, continuous swimming and intensive feeding practices—resulting in systemic physiological impairments such as compromised cardiac function, skeletal deformities, osmoregulatory and endocrine dysfunction, immune suppression, compromised skin and gill health, and a suite of production-related diseases. Moreover, the artificial stability of RAS does not supply the environmental variation necessary for developing the physiological resilience needed for successful adaptation to life at sea. These effects are particularly severe during smoltification, where current protocols fail to provide the environmental cues necessary for proper physiological transformation. The resulting “pseudosmolts”, while technically seawater-tolerant, lack the physiological robustness needed for thriving in marine environments. The trends towards the production of larger smolts has also proven counterproductive, with higher incidences of diseases like hemorrhagic smolt syndrome and nephrocalcinosis.

As a result of these fundamental biological conflicts, physiologically compromised fish ill-equipped for subsequent life stages are produced. These patterns mirror a defining global challenge in animal agriculture: the fish farming industry is repeating historical mistakes of terrestrial animal farming by prioritizing short-term efficiency at the expense of biological limits. Yet this recognition creates an opportunity: by treating biological requirements as non-negotiable parameters in system design and farming practices—such as ensuring adequate environmental cues for smoltification, introducing dark hours, and allowing periods of slower growth for skeletal and cardiac development—fish farming production can simultaneously achieve better welfare and reduce production risks.

These findings and their implications will be extensively detailed in our forthcoming book “The Life of Juvenile Salmon in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems“.

Chapter 1. Introduction to the Life of Juvenile Salmon in RAS

Chapter 2. Natural behavioral patterns of Atlantic salmon and fundamental constraints in RAS

Chapter 3. Challenges in maintaining water quality

Chapter 4. Biological challenges of intensification and fast growth rates.

Chapter 5. Smoltification in intensive production.

Chapter 6. Disease outbreaks

Chapter 7. Husbandry and Handling Operations

Chapter 8. Biological, Operational and Economic Constraints.

Chapter 9. Research Gaps in Salmon RAS Farming

Chapter 10. RAS welfare Impacts in other aquatic species

Chapter 11. Early Life Matters (a lot): welfare recommendations for the rearing of juveniles.

** Introduction of dark hours (with dawn and dusk)

** Slower growth in the hatchery phase to ensure proper development. Although slower-growing animals may live longer, they greater immune competence, resilience to diseases (production-related and infectious), to environmental stressors and other challenges means that a lower prevalence, severity and later onset of welfare issues (diseases, injuries) is expected, leading to a shorter overall time in states of pain and distress (similar to the positive welfare impacts of replacing fast- by slower-growing broiler birds in the farming of land animals).

** Refine smoltification protocols to allow full physiological transformation

** Design/engineer rest areas

** Change current velocity and direction over certain periods of time

** Implement mandatory reporting requirements, including data on prevalence of adverse outcomes.

** Develop audit systems.