Life in the wild is far from idyllic for most sentient organisms. Challenges such as disease, parasitism, predation, accidents, violent intraspecific conflicts, thirst and hunger, alone or combined, are experienced by nearly every wild animal at some point in their lives, and will kill most before adulthood.

Although the number of wild animals vastly exceeds the number of animals under human custody, efforts to reduce animal suffering are typically focused on the latter group. The daily experiences of wild animals are, to a great extent, out of the realm of direct human control. Different from efforts targeting the welfare of domesticated animals, there is much uncertainty on the potential ramifications of our interventions in the natural world. We can be confident that a number of farm animal welfare reforms (such as banning battery cages and promoting the use of slower-growing broiler strains) will positively affect the lives of billions of animals raised in industrial farming systems. However, which strategies would ensure the mitigation of pain from long-lasting ailments that an even greater number of wild animals endure as a result of injuries, disease, starvation, parasitism, or extreme weather conditions?

Under this perspective, efforts to mitigate wild animal suffering could be seen as hopeless, or worse, a diversion of resources from more tractable causes. We disagree. In the infinite turns and twists of human experience, there are opportunities to do and promote good in unexpected, diverse, and personal ways. Good actions that could be taken as frivolous in the ‘grand scheme of things’ can be steps in the right direction towards higher goals. When (human) families build nest boxes for wild birds with their children, not only are they providing shelter for nest box tenants, but also fostering their children’s empathy towards other sentient minds – the very empathy from which “doing good” can grow and multiply.

If reducing suffering in the wild is worth pursuing, the next question is how to do it effectively, and cost-effectively. One course of action proposed by one of the very few organizations working exclusively in this area, the Wild Animal Initiative, is the development of academic research dedicated to wild animal welfare – a very much needed strategy to enable gathering the evidence required to design effective solutions.

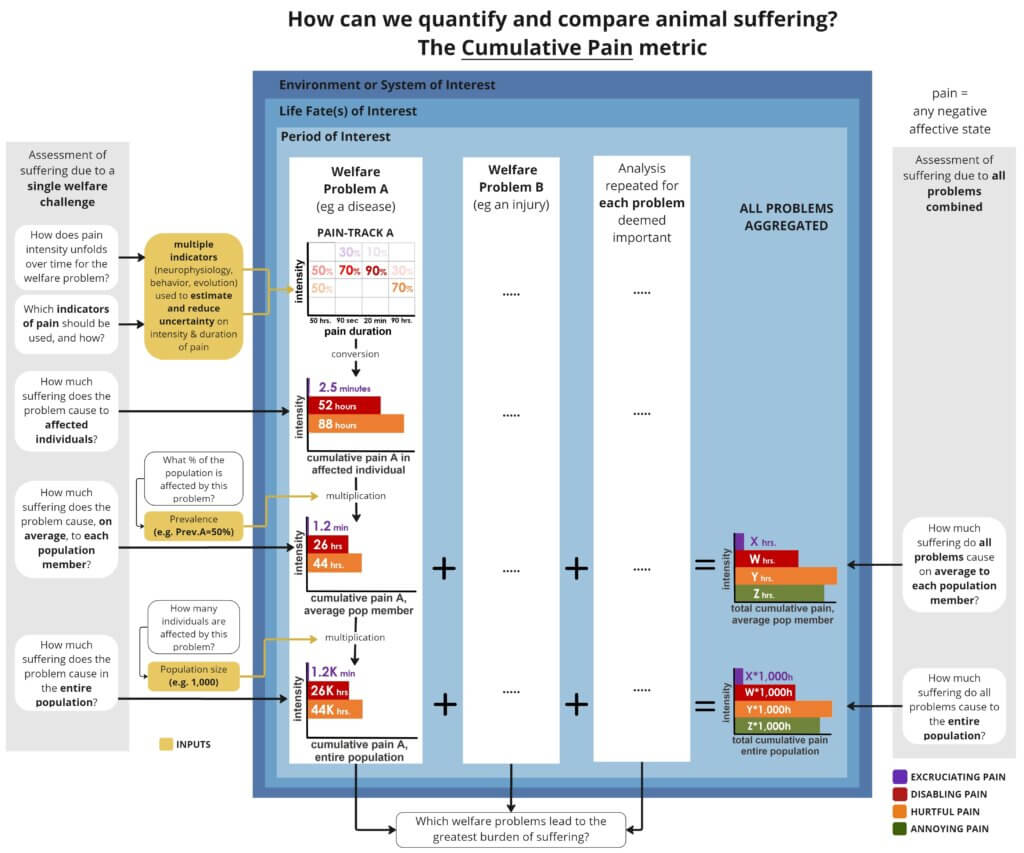

Although originally designed with intensively farmed animals in mind (to inform consumers on the welfare footprint of animal-sourced products), the Cumulative Pain metric (see method) can also be of assistance to studies on wild animal welfare. Briefly, it can be used to translate scientific evidence on the duration and intensity of the pain associated with major welfare challenges experienced by wild animals into time spent in pain of different intensities. The use of a universal and easily interpretable metric with biological meaning (time in pain) enables comparing the magnitude of suffering brought about by welfare challenges of very different natures (injuries, diseases, deprivations), or even by different species (see our FAQ).

The flowchart below illustrates the main analytical steps of the method and the type of questions that it addresses (an interactive version is available here):

In addition to enabling quantitative comparisons, an inventory of the magnitude of suffering associated with different challenges that wild animals typically endure can also promote awareness about wild animal suffering, help identify hotspots of suffering in the wild and, importantly, contribute to the design strategies to reduce suffering in the wild without burden shifting.

We consider a simple approach: the quantification of how much suffering is associated with different causes of death, all of which are experienced by most wild animal species.

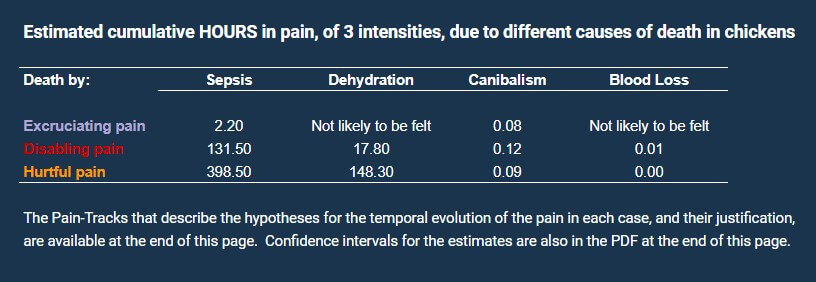

To illustrate it, consider first the estimates of presented on the Table below, on the cumulative time in pain of different intensities endured as a result of different causes of death: lack of water leading to death by dehydration, unresolved infections leading to sepsis, fatal attacks from conspecifics, and blood loss from having major arteries and veins cut or punctured.

Although these estimates of Cumulative Pain were established for a farmed species (laying hens and broiler birds), these causes are commonly associated with death in most wild animals. For example, in case of severe infections (a common occurrence in wild animals), death by septic shock is a frequent outcome. Likewise, blood loss (exsanguination) is typically the underlying cause of death in the case of predation and some injuries. Dehydration is also a frequent cause of death in cases of drought, dislodgement and disabilities that prevent water intake. And although triggered by a different mechanism (food shortages), intra-specific conflicts resulting in cannibalism are also observed in wild species. Even though estimates of Cumulative Pain experienced from these types of death are likely to vary across species due to differences in their metabolism, life-history traits and environment, general patterns are likely to be very similar (many of the pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical symptoms triggered by these challenges are shared across a wide range of vertebrates).

With that in mind, estimates in the table above suggest that events leading to death by blood loss (e.g., predation, some injuries) are likely associated with the least amount of suffering (an observation possibly counter-intuitive to the general public, as images associated with a violent death are typically more impacting). Yet, a slow death due to a generalized infection, for example, imposes a much higher burden of pain on individuals.

Similar patterns are expected in the case of non-fatal diseases, injuries and deprivations. For example, chronic hunger from feed restriction in broiler breeders is the greatest source of physical pain that any individual chicken experiences over her life. Likewise, malnutrition and starvation are expected to underlie a large fraction of the burden of pain endured by animals living in the wild. In general, long-lasting ailments (e.g. some forms of parasitism, locomotion-impairing conditions) are bound to be associated with a greater burden of pain.

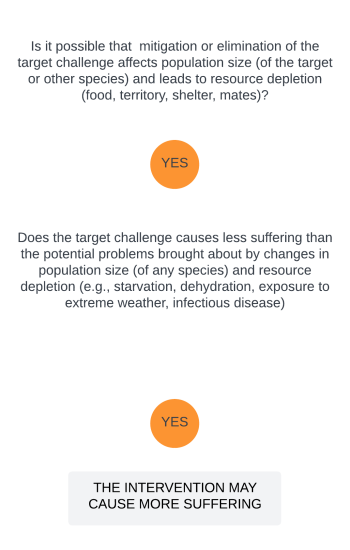

In the flowchart below we briefly explore how estimates of Cumulative Pain can be used in the assessment of the welfare impacts of interventions targeting wild animal species. Specifically, it illustrates one of the possible questions to determine the extent to which reducing the incidence of a target welfare problem in the wild, or eliminating it, can effectively reduce wild animal suffering.