Defining Affective Experiences

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso

The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact of each and every affective experience that the target animals endure over a timeframe of choice, as measured in terms of its intensity (how pleasant, painful, frustrating, or distressing it is) and duration (how long it lasts). The goal is to understand and compare the welfare of animals (i.e., the cumulative time spent in affective states of different intensities) across conditions and systems in a way that is both scientifically sound and useful. To do this, the WFF relies on a set of building blocks (note: we use initial capital letters for terms with operational definitions, described in this glossary):

In conducting any welfare impact analysis, one must first identify the multiple Affective Experiences that animals endure over their lives in the different scenarios analysed. The purpose of this text is to help users define which Affective Experiences should be analyzed and at what level of specificity. This involves finding a balance between biological plausibility, data availability, and the usefulness of the results.

One of the most critical steps in applying the Welfare Footprint Framework is deciding how Affective Experiences should be defined for analysis. This step determines the resolution of the welfare quantification—too broad, and important nuances may be lost; too detailed, and the analysis may become unmanageable or unsupported by data. The challenge lies in avoiding both oversimplification and unnecessary complexity.

Not enough detail

It is important to recognize that the appropriate level of detail will depend on the objective of the analysis. In some cases, the goal may require rapidly estimating the overall affective state of an animal during a given phase of life, such as the rearing or production phase. In such cases, it may be valid to use broad categories of experience—such as general discomfort or well-being—without distinguishing between every individual disease, deprivation, or positive event the animal may encounter. However, this type of broad estimation cannot be directly supported by empirical evidence on intensity and duration. That is because the scientific literature and field data provide validated indicators of intensity and duration only for specific conditions, such as fractures, respiratory infections, social bonding, or restricted movement.

To ensure that the analysis remains evidence-based, it is often necessary to define affective experiences at a more granular level. This means anchoring them in specific biological outcomes and pathways that are known to result in distinct experiences. Pain from a fractured limb, pleasure from affiliative interactions, or fear from predator exposure are all examples of experiences with documented affective relevance and measurable properties. These experiences are not only more scientifically tractable—they also tend to mark events that are especially meaningful in the life of the animal. They help characterize key welfare risks and opportunities.

Too much detail

At the other end of the spectrum, one may be inclined to define affective experiences in an overly detailed manner. This often happens when attempting to distinguish between every minor variation in symptom presentation or disease etiology, believing that more granularity necessarily equates greater accuracy. However, excessive granularity can make the analysis cumbersome and can exceed the resolution supported by available data. For example, differentiating between every possible cause of lameness, or treating slight differences in respiratory pathogen strains as separate experiences, may not yield meaningful distinctions in what the animal feels.

A similar issue arises when users define affective experiences based on symptoms (e.g., fever, coughing). This approach may appear detailed or clinically grounded, but it introduces unnecessary complexity and limits the usefulness of the analysis. Symptoms can indeed be part of an affective experience—such as coughing that results from a painful airway irritation —but they are often not reliable units of analysis on their own. Symptoms reflect observable aspects of a disease process, and their presence may suggest a certain intensity or progression.

Moreover, symptoms (or indicators – see this figure) do not provide a dependable basis for quantification. There is often no validated data on the duration and prevalence of individual symptoms in a population. For example, we might know how many animals suffer from tracheitis, and for how long, but we typically lack systematic data on how many animals cough, how frequently, and for how long in a way that can be used for quantification. Because symptoms are part of the unfolding of a disease over time, they are best viewed as indicators or inputs—useful in clinical judgment or diagnostic pathways. Additionally, the same symptom can appear across a range of very different conditions, and its affective relevance depends entirely on context. Coughing could reflect a temporary irritation or a necrotizing infection. Treating symptoms as affective experiences overlooks this variability and masks the differences in what the animal may actually feel.

Classifications based on Aetiology

Another common tendency is to define Affective Experiences in terms of the specific aetiology of a condition—for example, as “respiratory disease caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV),” or “respiratory disease caused by influenza virus,” or “respiratory disease caused by metapneumovirus.” While this level of detail might reflect a clinical interest in diagnosis, it is not helpful for affective experience analysis. First, population-level data on the prevalence of these specific viral causes is rarely available, as diagnostic testing is typically not performed routinely, especially in large-scale production systems. Second, these aetiologies often result in highly similar symptoms, and the affective experience they produce (such as irritation, air hunger, or fatigue) is often indistinguishable. In human health, a common practice is to refer to these overlapping presentations as “Influenza-like illness” (ILI), recognizing that the syndrome is more relevant to the patient’s experience than the precise pathogen. The same logic applies here: rather than defining separate affective experiences by each pathogen, it is better to define them at the level of the syndrome or biological outcome they share. This allows for more realistic, evidence-based estimates of intensity and duration, and avoids artificial fragmentation of experience categories.

Below we provide a set of principles to help users define affective experiences at a level of detail that is analytically sound, biologically meaningful, and operationally feasible for population-level welfare assessment

1. Group when experiences are similar in intensity and duration

Group biological outcomes into one affective experience only when they are likely to feel the same to the animal.

✅ Example: Several mild respiratory infections that all cause brief mucosal discomfort might be grouped.

2. Keep separate when affective experiences are qualitatively distinct

Even if two biological outcomes affect the same body system, they should be treated as separate affective experiences if the animal is likely to feel them differently.

✅ Example: Pain from a clean, well-aligned bone fracture should not be grouped with pain from a bone fracture with non-union that never heals and leads to chronic inflammation, even though both are classified as ‘bone fractures.’ The intensity of the pain caused by each type of fracture differ significantly. Defining them separately allows for more informative assessments, especially when comparing different housing systems, genetics, or management practices that affect the likelihood of one type over another.

3. Separate experiences that unfold differently in different animal groups

Even if animals share the same condition or behavioral opportunity, they may experience it differently depending on the pathway (e.g., acute, chronic, fatal), severity (e.g., mild vs. severe), degree of deprivation, or degree of fulfillment. Each distinct trajectory results in a different affective experience and must be analyzed as such..

✅ Example: Hens suffering from vent wounds due to pecking may follow different pathways: (1) Some heal spontaneously and experience short-term pain; (2) Others develop infections and chronic inflammation; (3) a few die due to complications from severe tissue damage. Each group must be modeled as having a distinct affective experience

✅ Example: All hens may have access to foraging, but the quality of the substrate matters: (1) Some peck at inert litter, receiving minimal sensory feedback, (2) Others forage in a rich substrate containing food particles and insects.

4. Base decisions on the level of detail supported by data

Sometimes, the theoretically ideal distinctions cannot be made because population-level data is not available. In such cases, broader groupings may be necessary.

✅ Example: Lameness in broilers can result from many causes. However, even when the underlying aetiology is the same, different birds may experience it in very different ways depending on the severity, location, and progression of the condition. Two animals with the same musculoskeletal issue might have completely different levels of discomfort, mobility restriction, or pain duration. Because welfare assessments often rely on gait scores, which integrate these aspects into an observable indicator, defining affective experiences based on gait score is both more feasible and more informative than trying to isolate every underlying etiology.

5. Make distinctions that are informative for welfare analysis

A key reason to define experiences separately is that it makes the quantification informative. If the goal is to compare the welfare consequences of two or more procedures, such as different vaccination methods, or environmental enrichments, the underlying affective experiences must be analyzed separately. Even if the tissue affected is the same or the outcome is similar in general terms, differences in how the condition is produced can lead to distinct experiences for the animal.

✅ Example: Pain from thermal dehorning with a hot iron should not be grouped with pain from chemical dehorning, even though both are procedures applied to the same area of the animal’s body. The mechanism of tissue damage, progression of healing, and likelihood of chronic pain can differ significantly between these techniques. Defining these experiences separately is also essential for evaluating and comparing their welfare consequences .

6. Avoid grouping based on symptoms alone

Symptoms such as coughing, lethargy, or poor feather condition may result from a wide range of biological outcomes and should not be used as the basis for defining affective experiences. A clear diagnosis, including an understanding of cause, location, and mechanism, is needed.

❌ Less Appropriate: Grouping all cases involving coughing as “Pain from coughing.”

✅ More Appropriate: Defining pain based on the underlying cause, such as “Pain from upper respiratory tract infection.”

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Confounding Factors in Welfare Comparisons of Animal Production Systems Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable

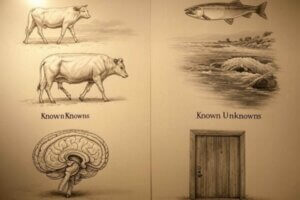

Borrowing the Knowns and Unknowns Framework to Reveal Blind Spots in Animal Welfare Science Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim There is always a risk of fixating on what we already