Defining Affective Experiences

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim

Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable conclusions in science. However, controlled experiments are not always feasible, ethical, or practical, and one must instead rely on retrospective analyses of existing datasets to uncover meaningful patterns.

This is particularly common in social sciences, psychology, public health, epidemiology, and economics, where large observational datasets are often used to infer causality. For example, in public health, studies on the long-term effects of smoking or the impact of pollution on respiratory diseases have relied on existing medical records and environmental data rather than randomized trials, which would be unethical.

A classic example of how careful analysis of observational data can overturn conventional wisdom is the work of Daniel Kahneman, whose research on cognitive biases and decision-making (Thinking, Fast and Slow) demonstrated that humans do not always behave rationally, as previously assumed in classical economic models. His work, which earned him a Nobel Prize in Economics, has often relied on retrospective analyses of decision patterns rather than controlled trials.

Similarly, Hans Rosling, in Factfulness, debunked widespread myths about global poverty and development trends by analyzing historical datasets. His work demonstrated that when adjusted for factors like GDP growth, access to healthcare, and education levels, many claims about worsening global inequality were not supported by the actual data.

In economics, Thomas Sowell has extensively applied this principle in his analysis of income disparities, educational outcomes, and social mobility. His work demonstrates how controlling for factors like education level, work experience, and family structure can reveal patterns that differ from popular assumptions, emphasizing the need for data-driven, rather than narrative-driven, conclusions.

The same principles apply to animal welfare research, where controlled experiments are often unfeasible or unethical, and researchers must rely on industry data, automated monitoring systems, and observational studies to assess welfare outcomes. As the use of precision livestock farming and automated welfare monitoring technologies (such as computer vision tracking, behavioral sensors, and real-time physiological monitoring) expands, retrospective analyses of these large datasets will become even more critical in drawing valid conclusions about animal welfare in different production systems.

Without careful adjustments, comparisons may incorrectly attribute welfare outcomes to production systems rather than to confounding variables such as differences in management decisions, economic investment, types of animals or life-stage differences.

Here we describe some common confounding factors in welfare comparisons, and possible analytical approaches to address confounding.

If economic and human resources are allocated differently among production systems, welfare comparisons can be skewed. Feedlots, for example, typically invest more in veterinary care per animal than pasture-based systems. This can lead to lower mortality rates in feedlots, not because the system is inherently better for welfare, but because intensive monitoring and interventions can reduce the likelihood of acute health crises. However, these interventions may also mask underlying welfare issues of similar or worse severity in feedlots than in pasture-based systems.

Selection biases occur when different production systems use different genetic lines or selectively place healthier animals in specific systems. In the beef cattle industry, for example, grain-fed feedlot cattle are often selected from breeds with greater feed efficiency, or that, depending on market prices and the animals’ general health, are deemed worthy of the investment on a feedlot at the finishing phase. A comparison of welfare outcomes between these groups must therefore account for the pre-existing and underlying differences in the health and resilience between the two groups of animals.

A critical confounding factor often overlooked is the animal’s developmental history and adaptation to specific environments. Production animals develop physiological and behavioral adaptations to their early rearing environments that significantly impact their ability to thrive when transferred to different systems later in life. Valid welfare comparisons must account for the congruence between rearing and production environments. A system that appears superior when populated with appropriately reared animals may perform catastrophically when housing animals with mismatched developmental histories. This understanding fundamentally challenges simplistic “system A versus system B” welfare comparisons. The welfare implications of any production system cannot be evaluated in isolation from the animal’s developmental trajectory. Meaningful comparisons must either match rearing environments to production systems or explicitly account for adaptation capacity as a welfare dimension in its own right.

A pervasive confounder in system comparisons is selective measurement of biological outcomes. Studies often focus on easily quantifiable biological outcomes like mortality, injuries, or production parameters while neglecting equally important biological outcomes such as behavioral and social deprivations or long-term health impacts. This selective inventory creates fundamental distortions in system evaluations. For example, early weaning practices in pig production may appear advantageous when measuring immediate post-weaning mortality and growth rates, while missing significant biological outcomes such as compromised gut development and impaired immune function. Valid welfare comparisons require clarity on the spectrum of biological outcomes considered across all relevant welfare domains in all systems considered.

Welfare comparisons across production systems are frequently confounded by unaccounted environmental and geographic factors that operate independently of the system design itself. Production systems situated in different regions experience fundamentally different environmental challenges that significantly impact animal welfare outcomes. Climate variations, for instance, can affect the welfare implications of outdoor systems—the same pasture-based approach might provide excellent welfare in moderate climates but create severe thermal stress in regions with extreme temperatures. Valid welfare comparisons must therefore either control for environmental variables by comparing systems within similar geographic regions or explicitly incorporate environmental challenges as contextual factors in the analysis.

Welfare comparisons across systems that raise animals with different lifespans present another challenge. Short-lived production animals may experience fewer cumulative welfare issues simply because they do not live long enough for severe outcomes to develop, or because their longer lifespan leads to greater time spent in negative states. This can create a false perception that high-turnover systems lead to better health than systems where animals live longer. One solution is to compare the quality of life of animals on an average day. Where life changes over the production cycle, average day life quality can be assessed at different points in time. The average day approach normalizes welfare assessments across a standard time unit, ensuring that the overall quality of life is assessed rather than just its duration.

In a meta-analysis of 6,040 commercial laying hen flocks across 16 countries, which examined mortality rates in conventional cages, furnished cages, and cage-free aviaries, we found that when the maturity of the system was controlled (i.e., the level of experience with the system), there were no significant differences in mortality between caged and cage-free systems. This finding challenges the previously widespread belief that cage-free systems inherently have higher mortality rates. Instead, our analysis demonstrated that the learning curve associated with managing these systems plays a crucial role in determining welfare outcomes.

Developmental history significantly confounds welfare comparisons across production systems. A clear example appears in salmon aquaculture, where fish reared in controlled Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) develop fundamental physiological and behavioral deficiencies that compromise their resilience in natural environments, where environmental variation and pathogen exposure are greater. When RAS-reared salmon are transferred to sea net pens, they can experience severe welfare outcomes including osmotic stress, immune suppression, and high mortality rates—not because sea pens are inherently worse for welfare, but because these fish are physiologically underprepared for marine environments. Their development in highly controlled conditions has effectively prevented the formation of crucial biological coping mechanisms necessary for survival in natural settings. This represents not merely a system quality difference but a permanent developmental limitation. Any valid comparison between RAS and sea net pen welfare outcomes must recognize that apparent system differences often reflect not just adaptation failures but irreversible developmental impairments created by early rearing conditions.

Mortality Rates in Farrowing Crates vs. Loose-Housing Systems: Some studies suggest that piglet mortality is lower in farrowing crates compared to loose-housing or outdoor systems, leading to the assumption that farrowing crates provide better welfare. However, this interpretation overlooks the welfare trade-offs for both the sow and piglets. Farrowing crates severely restrict the sow’s movement, preventing natural maternal behaviors such as nest-building and bonding with piglets, critical for sow welfare. Piglets raised by less-stressed mothers and with greater opportunities for behavioral expression may also benefit from greater resilience later in life, social coping ability and immune competence, leading to overall better welfare. This is also in line with research showing that improving maternal welfare improves disease resistance, and resilience of piglets.

Addressing confounding factors is crucial in animal welfare research to ensure meaningful results. Several approaches can be employed:

Within the Welfare Footprint Framework, the development of a proper veterinary inventory plays a crucial role in identifying the Biological Outcomes that arise from various Circumstances animals experience. However, establishing causal relationships between these Circumstances and the Biological Outcomes identified is challenging due to multiple confounding variables—elements that can obscure or distort true causal links. Recognizing this, we place special emphasis on controlling for confounders.

Animal welfare research must adopt transparent analytical approaches to ensure robust conclusions. Without such rigor, comparisons between production systems risk being biased by resource disparities, genetic differences, lifespan variations, differences in experience with the systems and environmental factors, or mismatches of rearing and growing conditions, leading to misleading conclusions. This review serves as a reminder that carefully accounting for these variables is not just an academic necessity but a practical imperative. By employing well-controlled comparisons, we can attain a more accurate and meaningful understanding of animal welfare impacts across different production systems.

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Confounding Factors in Welfare Comparisons of Animal Production Systems Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable

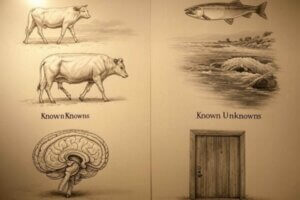

Borrowing the Knowns and Unknowns Framework to Reveal Blind Spots in Animal Welfare Science Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim There is always a risk of fixating on what we already