Defining Affective Experiences

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim

There is always a risk of fixating on what we already know while overlooking aspects of reality that might be equally or more important. Even science is not immune to this issue: often, research efforts—spanning years of publications and theses—make little meaningful progress because they remain confined to a “comfortable zone,” focusing on what is convenient to study rather than what is truly needed.

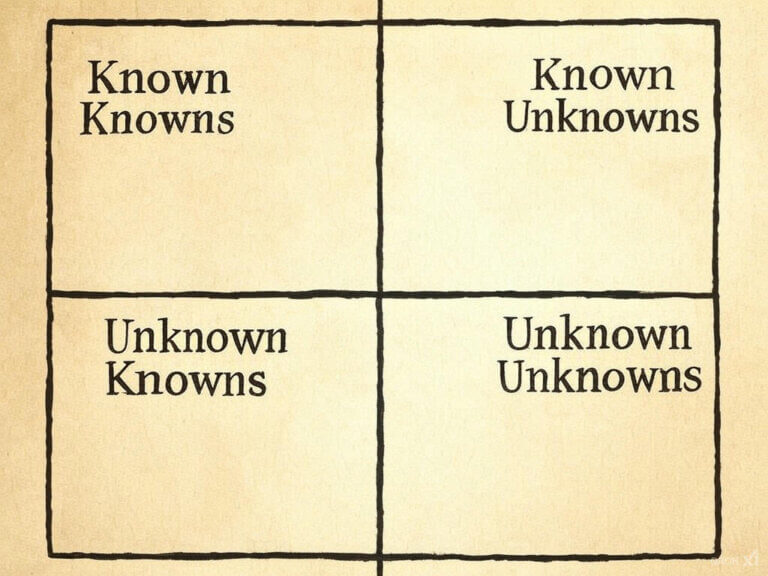

Donald Rumsfeld famously introduced the Knowns Unknowns framework for categorizing knowledge during his tenure as U.S. Secretary of Defense, specifically in the context of addressing uncertainty about whether Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction. Its roots trace back to earlier ideas in philosophy, psychology, and risk management: for instance, the Socratic concept of ignorance, which highlights the importance of acknowledging what we don’t know, and the Johari Window (1955), which categorizes knowledge about ourselves into what is known and unknown to oneself and others. In military strategy and decision-making, the framework assists in pinpointing both anticipated and unforeseen risks.

We believe this approach is equally valuable for animal welfare science. To counter this, one of the key components of the Welfare Footprint Framework is identifying putatively neglected sources of pain before describing and quantifying them. In this context, the Knowns and Unknowns framework serves as a valuable reminder to continuously question and challenge what we think we know. We share this perspective because we believe that each quadrant of this framework can be a useful tool for others studying or working to improve animal welfare.

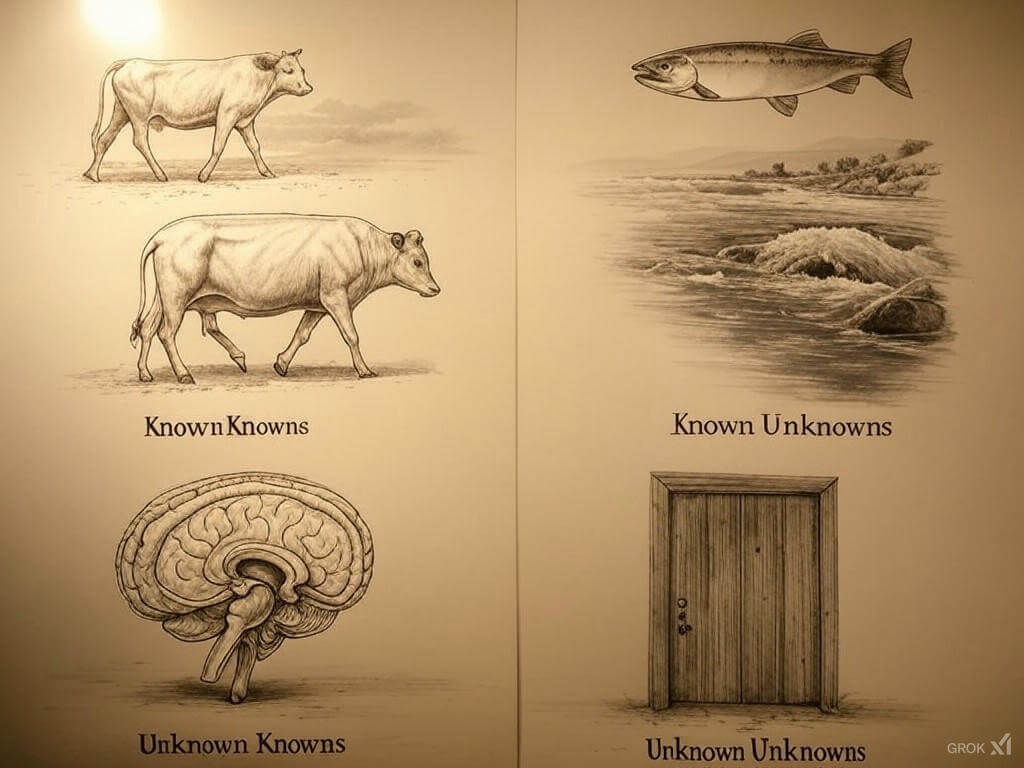

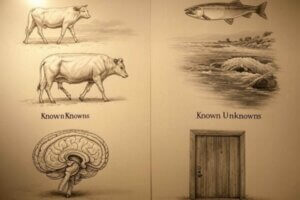

Figure 1. The Knowns and Unknowns Framework organizes knowledge into four quadrants: Known Knowns, where information is well-documented; Known Unknowns, where we acknowledge there are gaps in our understanding; Unknown Knowns, where knowledge exists but is not fully recognized or applied; and Unknown Unknowns, representing areas where we are unaware of what we don’t know

In animal welfare, Known Knowns are the well-established issues that have been thoroughly researched and widely acknowledged. These are problems where the causes, consequences, and solutions are clear.

A prime example is lameness in cattle, which has been extensively studied. The circumstances causing lameness—such as poor housing conditions, inadequate hoof care, and inappropriate flooring—are well understood. Its Biological Outcomes, including chronic pain, reduced mobility, and decreased productivity, are similarly well-documented. Furthermore, solutions such as better housing designs, regular hoof trimming, and improved flooring are widely recognized as effective interventions.

The challenge for Known Knowns lies in ensuring consistent application of solutions across production systems. While the science is settled in many cases, practical implementation often lags due to economic or logistical constraints.

Figure 2. This diagram illustrates the Knowns and Unknowns Framework applied to animal welfare science, with each quadrant representing a different category of knowledge: Known Knowns, where we have a clear understanding of issues like cattle lameness, depicted by a cow struggling to walk; Known Unknowns, where we acknowledge gaps in understanding, like the welfare of salmon; Unknown Knowns, where existing knowledge such as the brain’s role in emotion is not fully utilized, shown by a mouse brain’s sagittal plane; and Unknown Unknowns, symbolized by a door, suggesting hidden or yet-to-be-discovered welfare concerns. This diagram serves as both a conceptual map and a call to action for ongoing research and application in improving animal welfare.

Known Unknowns in animal welfare refer to problems that are recognized but not yet fully understood or addressed. These issues highlight critical gaps in data or knowledge that must be addressed to develop effective solutions.

For example, many of the circumstances that trigger different affective states in fish are Known Unknowns. While research has established that fish can experience physical pain and other negative affective states, including fear and anxiety, our understanding on how various circumstances—such as poor water quality, crowding, or sudden environmental changes— ultimately translate into negative affective experiences remains limited. Specifically, the relationship between the perception of these circumstances by fish and the physiological and affective consequences they endure is not yet fully mapped.

Unknown Knowns represent knowledge that exists but has not been fully integrated into animal welfare science or applied in practice. These gaps often arise due to insufficient communication between researchers in different fields and, ultimately, scientists and animal advocates.

One particularly striking example is the neurological basis of affective states in animals. Pioneering neuroscientists such as Jaak Panksepp and Mark Solms have conclusively demonstrated that emotions like fear, joy, and pain originate from specific areas of the brain—particularly the primitive brainstem and midbrain structures—which are shared across a wide range of species. This robust body of evidence provides a clear foundation for understanding the emotional capacities of animals, yet it has not been fully embraced or utilized to comprehensively map these capacities in welfare assessments.

This gap in integration has significant implications for animal welfare. The ability to compare the capacity to experience affective states across species is fundamental to determining the moral weight of their suffering. It is also an important element for calculating the Welfare Footprint of animal products when interspecific considerations are involved. For example, weighing the welfare impacts of farming chickens versus salmon requires a clear understanding of potential differences in their emotional capacities (should one hour of Disabling pain have the same moral weight in both species? Can those groups of animals actually experience pain at those levels?).

Recognizing the importance of this issue, we at the Welfare Footprint Project are actively examining how this knowledge can be applied to interspecific welfare comparisons. This will be a critical component of future contributions, where we aim to provide practical methodologies for incorporating these insights into welfare assessments. Fully integrating the neurological basis of affective states into welfare science should facilitate more comprehensive and ethically grounded approaches to improving animal well-being.

Unknown Unknowns are the greatest blind spots. In animal welfare science, these represent welfare issues that have not yet been detected or understood, often due to limitations in current methodologies, gaps in data collection, or the inherent complexity of biological systems. By their very nature, these issues are difficult to predict or define, but they hold the potential to profoundly impact the welfare of animals.

While the specifics of these Unknown Unknowns remain speculative, parallels from human medicine might provide valuable insights. In humans, countless illnesses and conditions manifest subtly or remain undiagnosed due to diffuse and variable symptoms or the lack of adequate diagnostic tools. It is reasonable to assume that many conditions and forms of suffering in animal populations remain similarly hidden or inaccessible to current methods of observation and analysis.

It is interesting to note that this is an area where artificial intelligence (AI) may be of great value. AI excels at analyzing vast and complex datasets, uncovering patterns and anomalies that might otherwise escape human observation. By integrating data from multiple welfare indicators—such as behavioral changes, physiological markers, and environmental risks—AI can detect early warning signs of poor welfare and identify previously unknown patterns of suffering.

For example:

It is likely that the most significant sources of welfare loss in the most extensively studied farm species have already been identified. These include chronic pain caused by ailments associated with rapid growth and excessive productivity, chronic social stress from overcrowding, and painful routine procedures like tail docking, surgical castration, and beak trimming. However, even in these well-researched areas, we must remain vigilant. Surprising findings continue to emerge. For instance, in our analysis of broiler chickens, we initially assumed that their primary welfare burden, for individual chickens, would stem from physical ailments like lameness. However, we found that chronic hunger among breeder chickens—who are deliberately underfed to control growth—was actually the most significant source of welfare loss.

In pursuing the main goal of the Welfare Footprint Project, how do we account for the limitations of what we don’t yet know? When quantifying the Welfare Footprint of specific practices, production systems, or animal-based products, how can we ensure that potentially critical welfare aspects are not unintentionally overlooked?

Our solution is radical transparency regarding the scope and limitations of each analysis. Given the complexity of animal production systems, it is crucial to explicitly declare which key aspects—such as Life-Fates, Life-Phases, and Affective States—were included in the Welfare Footprint analysis. By doing so, we also make it clear what has been left out, ensuring that any potential gaps in knowledge are visible, rather than implicit or hidden.

For example, in our notation system (which we will detail in a future post), the Welfare Footprint of an egg will indicate:

By making these factors explicit, we enable meaningful comparisons between results and ensure that the scope of each analysis is clearly defined. Just as importantly, this approach creates transparency about what was left out, allowing researchers, policymakers, and advocates to recognize these Unknowns and work toward addressing them in future assessments. In doing so, we strengthen the scientific and ethical foundation of welfare evaluations, ensuring that no source of suffering goes unnoticed simply because it was not yet considered.

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Confounding Factors in Welfare Comparisons of Animal Production Systems Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable

Borrowing the Knowns and Unknowns Framework to Reveal Blind Spots in Animal Welfare Science Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim There is always a risk of fixating on what we already