Defining Affective Experiences

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Cynthia Schuck-Paim; Wladimir J. Alonso; Cian Hamilton

The Welfare Footprint framework quantifies the cumulative load of affective experiences an individual, or population, experiences over a period of time. Although applicable to affective states of positive and negative valence, it is primarily focused on the latter. Here, evidence-based estimates of the time spent in pain of four intensities (Annoying, Hurtful, Disabling, and Excruciating) are used to quantify suffering in different scenarios, and thus help prioritize among welfare interventions. However, in some cases trade-offs may arise between brief intense suffering or longer lasting suffering of a milder intensity. Here we review the extent to which existing evidence could be used to establish a weighting system between pain intensity categories, hence a single scale of suffering.

Here are some key take-aways:

* The perceived unpleasantness of pain, as subjectively rated on pain intensity scales, escalates disproportionatelly with these ratings, suggesting that experiences of more severe unpleasantness feel disproportionately worse compared to their placement on a typical scale.

* Determining the exact form of the relationship, however, is still challenging, as insights from human pain studies are limited and difficult to apply to animals, and designing experiments to address this issue in animals is inherently challenging.

* Pain Intensity weights are likely dynamic and modulated by multiple factors, including interspecific differences in the perception of time. The very relationship between pain aversiveness and intensity ratings may change depending on the experience’s duration.

* Currently, the uncertainty associated with equivalence weights among pain intensity categories is orders of magnitude greater than the uncertainty related to other attributes of pain experiences, such as their prevalence or duration.

* Given these challenges, we currently favor a disaggregated approach. Disaggregated estimates can currently rank most welfare challenges and farm animal production scenarios in terms of suffering.

* In the case of more complex trade-offs between brief severe pain and longer-lasting milder pain we suggest two approaches. First, ensuring that all consequences of the welfare challenges are taken into account. For example, the effects of long-lasting chronic pain extend beyond the immediate experience, leading to long-term consequences (e.g., pain sensitization, immune suppression, behavioral deprivation, helplessness, depression) that may themselves trigger experiences of intense pain. The same may happen with experiences of brief intense pain endured early in life. Second, once all secondary effects are considered, we suggest examining which weights would steer different decision paths, and determining how justifiable those weights are. This approach allows for normative flexibility, enabling stakeholders to rely on their own values and perspectives when making decisions.

Pain, both physical and psychological, is an integral aspect of life for sentient organisms. Pain serves a vital biological purpose by signaling actual or potential harm or injury, prompting individuals to avoid or mitigate the cause of pain [1]. It varies in intensity (where intensity denotes the unpleasantness or aversiveness experienced by an individual, not intensity of physical stimuli), from a mild annoyance to an excruciating agony, and duration, from fleeting moments to persistent, long-lasting conditions. This diversity in the intensity and duration of pain also serves the adaptive purpose of guiding priorities [1,2]: while an acute, sharp pain demands immediate attention, a chronic, dull ache reminds individuals of a lingering issue that, though not urgent, can also have multiple and serious consequences if not attended to.

While the function of pain as a biological alarm system is clear, its implications on overall well-being are more complex. Does a short-lived yet intense agony compromise well-being more than a prolonged but more moderate discomfort? For instance, farmed animals endure brief yet harrowing experiences, such as surgical castration without anesthesia or some slaughter practices, which are intensely painful but relatively quick. Contrast this with the more moderate, but continuous discomfort of being in an overcrowded space over several months. Both situations detrimentally affect welfare, but understanding which causes more distress, or if they can even be directly compared, is needed to make informed choices that prioritize welfare effectively [3].

In their quest to maximize fitness, organisms often operate on heuristic principles, prioritizing immediate or more intense threats based on simple rules of thumb, rather than a comprehensive evaluation of all potential consequences over a longer time frame [4]. This might mean, for instance, giving priority to pain of higher intensity, everything else being equal. However, in the realms of human and animal welfare, the goal is often to establish a metric that considers overall welfare over longer time frames, enabling the prioritization of actions that minimize suffering without burden shifting.

Within the Welfare Footprint framework [5], the intensity (unpleasantness) of negative affective experiences (referred to as ‘pain’ for simplicity) is categorized into four levels (Annoying, Hurtful, Disabling, and Excruciating) and welfare loss, or ‘suffering’, is expressed as total time spent in each intensity category (‘Cumulative Pain’). In this way, the method adopts a pragmatic stance by expressing outcomes across pain intensities over time without conflating them into a single metric. By doing so, it acknowledges the challenges and inherent uncertainties involved in comparing different pains across their dimensions, at the same time offering actionable, evidence-based results that can be used for the pursuit of different priorities (e.g., those prioritizing the relief of the worst kinds of preventable suffering can focus only on estimates of time in Disabling and Excruciating pain). Still, considering that this research area holds scientific and practical value, our focus here is to contribute to discussion in this direction.

We start by approaching the prioritization dilemma that may arise in the presence of a trade-off between brief and intense suffering versus longer lasting suffering of a milder intensity. One way to investigate this question would be to explore, quantitatively, the aversiveness caused by different levels of pain intensity, and how these differences can be offset by varying durations. How long must an individual endure an annoying or hurtful discomfort for it to be equivalent to a few hours of disabling pain? Or more generally, how do intensity and duration relate? ? In other words, is it possible to convert categories of pain intensity from an ordinal to a ratio scale?

Experimentally ascertaining whether severity or duration has a greater impact on the welfare of animals presents many challenges [6,7]. Although many studies have assessed pain intensity in animals and non-verbal human subjects (typically through the use of observational pain scales that score behaviors such as muscle tension, posture, head position and facial expressions), these studies are silent with respect to the trade-off between the intensity and duration of pain. During a workshop organized by Rethink Priorities [8], experts convened to discuss potential experimental strategies for evaluating this question [7]. Several barriers were identified, including the difficulties in ensuring external validity given the impossibility of replicating the severity and duration of animal experiences, the hidden nature of affective states [9], the fact that animal behavior and preferences will not necessarily align with their long-term welfare interests, and the lack of sensitive and specific biological markers of cumulative affect [7].

Given the complexities of studying pain in non-human animals and the common evolutionary role of pain in sentient beings, an attractive approach is to pivot towards human studies. Humans share fundamental neurological and physiological systems with other animals, and have the capacity for self-reporting, which greatly simplifies data-collection. Despite the potential for bias in self-reporting [10], understanding how humans navigate this trade-off, or at least the degree to which the most intense pains are perceived as more aversive compared to lesser ones [7], may provide a valuable starting point.

Therefore, we start by reviewing the extent to which empirical evidence in human studies could be potentially used in welfare prioritization when trade-offs between intensity and duration are present.

In the domain of human research, various efforts exist to quantify the relationship between states of well-being. This is especially pronounced in global health, where understanding the impact of different health conditions, as determined by their severity and duration, is crucial for defining resource allocation policies.

Accordingly, health metrics such as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) integrate in a single cardinal scale the time spent in a health state with the severity of the state, or its ‘disability weight’, which varies from 0 (perfect health) to 1 (death) [11]. Inferences of disability weights can be conducted in different ways, from paired comparisons of preferences for hypothetical health conditions, to assessment of the time one would trade from perfect health to avoid a particular health state [12]. In all cases, however, estimates are derived from multiple dimensions of health states (e.g., mobility, level of functioning, anxiety and depression, pain, and self-care), many of which are not necessarily associated with affective experiences, but rather with cultural and social perceptions of the states evaluated that are not relevant to animals. Also, participants in these studies often judge health states they have not personally experienced, relying instead on their perception of what the experience might feel like, leading to multiple potential biases [10].

One potentially promising strategy would thus involve conducting extensive surveys where participants from diverse backgrounds, who experienced the events evaluated, make comparisons between painful (affective) experiences of varying intensities and durations. This was the approach adopted by the Qualia Research Institute in a study that asked participants to quantitatively compare their most extreme negative experiences relative to each other [13,14] . Most participants rated their most intense painful experience as at least three times more intense than the second most intense [14]. The results resembled what one would expect if the subjective experience of pain were scaled in a logarithmic manner, with large differences between intensities. Still, biases that cause people to recollect experiences (especially extreme ones) very differently from how they were perceived at the time were not addressed. These effects can be so large that they may wash out the real effects of the nature of experience [10,15]. A famous example of such a bias is the Peak-End rule [16], namely the consistent observation that the peak of an experience and how it ends play important roles in determining how the experience is remembered. For example, if a painful procedure is prolonged by adding a period of less intense pain, it is retrospectively evaluated as less painful, even though it entailed more overall pain [17,18].

Given these constraints, in the next section we focus on studies that directly assess pain severity perceptions from participants currently experiencing or having recently undergone specific painful conditions.

Upon reviewing the literature, we found that studies directly assessing pain severity perceptions from participants currently experiencing or having recently undergone specific painful conditions are surprisingly scarce. In an assessment of low back pain [19], patients were asked the number of years in each state they would exchange for resolution of their symptoms. All patients were willing to trade a disproportionately larger number of years to avoid a more severe pain state. Specifically, the perceived aversiveness of back pain increased non-linearly with severity (ratio severe to mild pain = 12:1). Another study used a similar methodology with chronic pain patients [20], estimating the disutility of mild, moderate and severe chronic pain as, respectively, 0.04, 0.14, and 0.26 in a paper test, and as 0.16, 0.26, and 0.27 when interviewed face to face.

The observation that disproportionately longer durations are required to compensate for increases in pain intensity once more suggests that the aversiveness of pain increases super-linearly with intensity (i.e., high-intensity pain is disproportionately more unbearable than moderate pain). However, in all cases the aversiveness of the chronic conditions evaluated may have been to some extent confounded with simultaneously occurring disabilities and socio-cultural ramifications of pain, unlikely to be present in non-human species. We therefore searched for studies evaluating instances of acute pain. Two studies were found. One examined pain intensity experienced by women during labor or recently after delivery [21]. The authors report a preference for moderate pain (level 5 out of 10) for two hours over extreme pain (10/10) for 1 hour. Additionally, a prolonged but mild pain episode (18 hours at 1/10 intensity) was favored over an intense but shorter bout of pain (2 hours at 9/10). Although the methodology does not enable establishing the numerical equivalence among pain ratings, an intensity scored as level 10 was perceived as being more than twice as bad as one scored level 5, as was a score 9 perceived as worse than 9 times as bad as a score of 1.

The second study investigated postoperative pain and cancer pain [22]. Here, the relationship among seven categories of pain (2: just noticeable, 3: weak, 4: mild, 5: moderate, 6: strong, 7: severe, 8: excruciating) was best described by a power function of the form y=0.99*x^2.99 for patients with postoperative pain and a power function of the form y=1.1*x^2.14 for patients with chronic cancer pain, where x corresponds to the pain category (1 to 8) and y the perception of intensity/distress. This translates into a perception of intensity for the seven categories of respectively 1, 8, 25, 62, 122, 210, 333 and 496 (postoperative pain) and 1, 5, 12, 21, 34, 51, 71 and 94 (cancer pain).

We find that the latter studies are possibly the most informative on the potential temporal equivalence among pain intensity levels. In addition to being exclusively focused on pain, they were the only studies assessing painful conditions by patients experiencing the pain. We find it unlikely that the most intense pain experienced is of an Excruciating nature as defined in the Welfare Footprint framework, since this category is by definition associated with extreme and unbearable pain, not tolerated even if for a few seconds (a definition which does not coincide with the description of the patients in the studies above). But if the most intense pain, as evaluated in these studies, corresponded to the ‘Disabling’ category, the equivalence between Annoying and Disabling pain would be best represented by a ratio of approximately 1 to 94-496.

The observation that pain’s aversiveness escalates super-linearly with intensity coincides with findings from experiments in psychophysics, a discipline that investigates the relationship between the physical intensity of stimuli and their subjective perception [23]. Research in this area indicates that as sensations, including pain, increase in intensity, their perceived aversiveness grows exponentially [24]. For instance, as the intensity of an electric shock rises, perception of the pain grows at an accelerating rate, so the hardest shock can feel over 3,000 times worse than the mildest [25]. Likewise, in humans exposed to contact temperatures between 43°C and 51°C, the worst pain was judged to be 4,000 to 25,000 times more intense than the mildest pain [26] [27]. The non-linear nature of pain perception is further illustrated by Gómez-Emilsson [13] through examples such as the Scoville scale (a scale that measures the spicy heat of chili peppers in heat units) and the KIP scale to rate cluster headaches, both assumed to be logarithmic in nature.

These findings are also aligned with evolutionary reasoning. Intense pain demands immediate cognitive prioritization, putting other functions on hold to ensure that, in the presence of potentially fatal threats, an organism’s primary objective is the mitigation of the pain source. By making the experience of intense pain overwhelmingly aversive, organisms are compelled to take swift action, increasing the odds of survival. Additionally, the threat to an organism’s survival is likely to increase exponentially with the severity of the harm. For example, while minor injuries are typically manageable and heal, critical thresholds can be crossed with harms of greater severity, overwhelming the body’s compensatory capacities. Severe injuries can lead to blood loss, organ failure, or infections, each exponentially increasing the risk of mortality. Moreover, the energy required for recovery from severe injuries can rapidly deplete the body’s reserves, reducing the ability to withstand additional threats and creating a cycle of increased susceptibility to further harm. Inflammatory and immune responses can also become detrimental with more severe harms, as excessive inflammation can damage healthy tissues and lead to a feedback loop that accelerates the impoverishment of welfare. These responses are also consistent with the observation that higher pain intensities have a disproportionately larger impact on human functioning than lower pain intensities [28,29].

Nonetheless, defining this relationship’s precise nature, remains fraught with uncertainty. In addition to empirical evidence being surprisingly scarce, intensity weights are likely dynamic and modulated by multiple contextual factors. For example, whether pain is delivered in short bursts or continuously seems to play a pivotal role in determining its relative unpleasantness [30]. In general, the perceived aversiveness of pain will be modulated by a myriad of factors that include its type, anatomical distribution, attentional states, anticipation, past experience and fear [29,31–33].

Other layers of complexity are also present. For example, pain itself might distort an individual’s perception of time [34]. Does enduring a certain level of pain for a shorter duration feel longer than a lesser pain endured for the same period? Similarly, relative weightings between categories of pain could vary among species. The ratio of how much worse ‘Excruciating’ pain is compared to ‘Annoying’ pain may differ for an insect, a fish, a cow, or a human [35,36], particularly in the presence of species-specific differences in the subjective perception of time [34,37,38]. In fact, the very relationship between the aversiveness of pain and its intensity may itself change depending on the duration of the experience. With no data to understand how this happens, the extent to which extrapolating from short to long intervals is valid is unclear, speaking against the use of fixed equivalence levels among pain intensity levels.

The non-linear nature of the relationship between pain intensity, as measured on orginal scales, and its corresponding aversiveness also means that even small errors in estimates of more intense pain have disproportionately larger effects in aggregated estimates of time suffering. To see this, consider the example in Table 1. Disabling pain is used as a reference, hence hypothetical equivalence factors represent the time needed in the other intensity categories that would make them as unpleasant as Disabling pain. As shown, there is a striking disparity in the contributions of different pain intensity categories to the final aggregated estimate. If Excruciating pain is assumed to be 10 to 1,000 more aversive than Disabling pain, estimates of time in Excruciating pain would account for over 90% of the aggregated estimate. Naturally, any imprecision in the estimated time in Excruciating pain would have a major impact on the aggregated results.

Table 1. Hypothetical weighting schemes: time units in each pain intensity category needed to make the experience as unpleasant as one time unit of disabling pain.

Category | Estimated time in pain at each intensity | Hypothetical Equivalence with Disabling pain | Time in Disabling- equivalent pain | Contribution of time in each intensity to aggregate estimate (%) |

Annoying | 10 minutes | 1/(100 to 1,000) | 0.6 to 6 sec | 0.001 to 0.0094% |

Hurtful | 10 minutes | 1/(5 to 100) | 6 sec to 2 min | 0.020 to 0.094% |

Disabling | 10 minutes | 1 | 10 minutes | 0.10 to 9.42% |

Excruciating | 10 minutes | 10 to 1,000 | 1.6 to 166.6 h | 90.45 to 99.88% |

Aggregate Estimate: time in Disabling-Equivalent Pain | 1.8 to 167 h | |||

These observations could also lead to the conclusion that efforts on preventing cases of intense suffering should possibly dominate most utilitarian calculations [13]. However, while the nature of reactions to intense pain is shaped to be overwhelming and disproportionate, prolonged suffering of more moderate intensities is not necessarily less detrimental to overall welfare. In fact, enduring moderate pain over an extended period will typically affect an individual’s health and quality of life in a manner that exceeds what might be expected based on duration alone. For example, chronic pain can alter pain pathways and make other pain experiences more intense, both by exacerbating the pain experience and reducing the threshold for future pain [39]. Likewise, chronic pain is associated with alterations in neurochemical and hormonal levels, reducing the ability to cope with stress and making individuals more vulnerable to disease [40]. Long-lasting pain can also lead to anxiety, depression, and helplessness, and prevent, partially or completely, positive affective experiences. Finally, experienced durations of moderate pain are often many orders of magnitude longer that those associated with intense pain.

In light of the complex interplay and cumulative impacts of chronic and acute experiences on overall well-being, comprehensive assessments of welfare that encompasses the effects derived from these experiences is essential for making informed decisions between interventions aimed at alleviating short-term intense suffering versus long-term moderate suffering. For example, in deciding between investing into banning experiences such as bodily mutilations or some slaughter methods versus longer-term issues such as high stocking density or confinement, an investigation of all the consequences of these practices would be required.

Effective resource allocation and prioritization among sources of suffering requires finding ways to quantify their burden in a comparative way. In the Welfare Footprint framework, the cumulative load of negative affective experiences endured by animals are quantified using a biologically meaningful metric: time spent in pain of four intensities. This granulated view of suffering is clear and intuitive and can be traced back to evidence, aiding resource allocation and decision-making processes targeting different priorities. Currently, disaggregated estimates can also rank most welfare challenges and farm animal production scenarios in terms of suffering

Yet, challenges arise when this (or other metrics) are asked to balance the intensity and duration of suffering. Foremost among these is the uncertainty associated with equivalence factors, which are needed for converting time spent in different intensity levels to a common metric. So far, these factors are not empirically substantiated, and carry high levels of uncertainty.

Additionally, with aggregate estimates of time suffering, references to the actual experiences of animals are lost. While estimates of 10 minutes in Excruciating or Disabling pain are readily understandable by any audience, aggregate estimates of time in pain do not have an intuitive meaning. For example, it is not clear if a long time in Disabling-equivalent pain is dominated by experiences of chronic or acute suffering, or some combination thereof. Likewise, there is also an ethical puzzle regarding the validity of balancing different levels of suffering [41]. For example, aggregate estimates of time in pain in a population with individuals enduring intense pain could be similar to that of a population where no individual suffers intense pain, but a larger fraction of individuals experience milder pain for a sufficiently long time. The extent to which extreme suffering concentrated in fewer individuals can be compensated by milder suffering in a large number of individuals is unclear.

In short, the seemingly straightforward concept of a weighting system between pain intensities is still riddled with limitations. Until equivalences in the dimensions of pain are better understood, we favor a disaggregated approach. In its current form the Welfare Footprint framework can rank most events, scenarios and systems. Where difficult trade-offs are present, the framework can be extended further by examining which weights would steer different decision-making paths, and then determine whether such a weight is scientifically justifiable.

We illustrate this possibility by considering estimates of Cumulative Pain, at each intensity, for some of the most common welfare challenges commercial chickens experience over their lives, including slaughter (Table 2).

Table 2. Measures of Cumulative Pain in chickens (estimated seconds in pain, at each intensity). Estimates correspond to the midpoint of uncertainty intervals [42,43], and do not consider the welfare impacts of the secondary effects of the harms described. ‘Average flock member’: estimated time in pain weighted by the prevalence of the problem (considers that not all individuals experience the problem, and/or experience different degrees of severity). ‘Worst possible case’: individual enduring the worst possible outcome.

Seconds in Pain | Hurtful (1) | Disabling (2) | Excruciating (3) |

(A) Effective electrical waterbath stunning in broilers (average flock member) | 62 | 70 | 1 |

(B) Electrical waterbath set to low carcass damage (average flock member) | 68 | 156 | 70 |

(C) Electrical waterbath stunning (any form) (worst possible case: conscious until scalding) | 154 | 367 | 116 |

(D) Lameness in fast-growing broilers (average flock member) | 805,464 | 193,068 | 0 |

(E) Lameness in fast-growing broilers (worst possible case: gait score 5 at slaughter) | 1,384,200 | 1,591,920 | 0 |

(F) Chronic hunger in fast-growing broiler breeders (all individuals assumed to undergo same experience) | 15,014,160 | 7,056,000 | 0 |

(G) Behavioral Deprivation in caged hens (all individuals assumed to undergo same experience) | 10,930,500 | 1,165,500 | 0 |

(H) Depopulation and Transport in cage-free hens (average flock member) | 41,184 | 90,180 | 2 |

(I) Keel bone fractures in cage-free hens (average flock member) | 5,201,352 | 371,952 | 0 |

(1) pain that disrupts the ability of individuals to function optimally; (2) continuously distressing pain that takes priority over most behaviors (drastic reduction of activity and inattention to other stimuli); (3) extreme level of pain that would not normally be tolerated even if only for a few seconds.

The table shows that for an intervention that reduces extreme forms of suffering during slaughter (chiefly Excruciating pain) to be favored over one that averts less-intense suffering (including problems such as lameness in fast-growing broilers, chronic hunger in breeders or behavioral deprivation in caged hens), Excruciating pain would need to be perceived as being many orders of magnitude worse than Disabling or Hurtful pain. For instance, the average broiler stunned with electrical parameters set to reduce carcass damage (i.e., less effective at causing loss of consciousness, row ‘B’ in Table 2) endures about 70 seconds of Excruciating pain, while lameness causes, on average, 1,384,200 and 1,591,920 seconds of Hurtful and Disabling pain, respectively (‘D’). To justify prioritizing improvements in electrical stunning parameters over enhancements in lameness based solely on the reduction of suffering, the aversiveness of Excruciating pain would need to be perceived as approximately 3,000 times more severe than Disabling pain, or over 14,000 times more severe when considering the Disabling and Hurtful pain together. When comparing the most severe outcomes—birds that are scalded alive during slaughter (‘C’) against those suffering from the most severe form of lameness, with a gait score of 5 at the time of slaughter (‘E’)—the perceived aversiveness of Excruciating pain would need to be about 13,000 times greater than that of Disabling pain to justify a focus on stunning reforms over lameness improvements. Similarly, for interventions aimed at enhancing stunning parameters (‘B’) to be deemed more beneficial to welfare than those targeting the mitigation of chronic hunger in fast-growing female broiler breeders (‘F’), the aversiveness of Excruciating pain would need to be considered over 300,000 times worse than that of Disabling or Hurtful pain.

In determining the plausibility that Excruciating pain is several orders of magnitude more averse than pain intensities that are still very distressing (such as Disabling pain), it is also necessary to consider that estimates of the welfare impacts of the farm-level harms described, such as lameness, behavioral deprivation and chronic hunger, do not include their secondary effects. For example, in the case of chronic hunger, secondary effects emerging from feed restriction include aggression, higher incidence of feather pecking, skin lesions, foot pad lesions, disrupted resting, impaired immunity and long-term consequences for the welfare of offspring (meat chickens) through epigenetic effects [43]. In the case of lameness, by-products include a greater risk of infection, dehydration, contact dermatitis, the frustration to perform highly motivated behaviors and sleep disruption [43]. Should these effects be considered, they would require an even higher aversiveness ratio for Excruciating pain compared to Disabling and Hurtful pain.

While these observations align with the view that interventions targeting prolonged suffering may warrant prioritization absent evidence that the welfare impact of intense brief pains exceed more moderate pains by orders of magnitude [7], we suggest that in case of difficult trade-offs decisions should be determined on a case-by-case basis, considering species-specific pain responses, context of decision, and full range of welfare effects associated with the intervention. For instance, while the secondary effects of intense suffering at slaughter does not have lasting secondary effects due to the immediacy of death, intense brief suffering at early life (e.g., bodily mutilations) are likely to have multiple and profound welfare consequences, such as heightened pain sensitivity and reduced stress resilience.

1. Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150: 971–979.

2. Cervero F. Understanding Pain: Exploring the Perception of Pain. MIT Press; 2012.

3. Broom DM. Animal welfare: concepts and measurement. J Anim Sci. 1991;69: 4167–4175.

4. Gigerenzer G, Gaissmaier W. Heuristic decision making. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62: 451–482.

5. Alonso WJ, Schuck-Paim C. The Comparative Measurement of Animal Welfare: the Cumulative Pain Framework. In: Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ, editors. Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens. Independently published. https://tinyurl.com/bookhens; 2021.

6. McAuliffe W, Shriver A. The Relative Importance of the Severity and Duration of Pain. Open Science Framework Preprints. 2022. Available: https://osf.io/ezvr2/

7. McAuliffe W, Shriver A. Dimensions of Pain Workshop Summary and Updated Conclusions. Rethink Priorities; 2023.

8. Rethink Priorities. In: Rethink Priorities [Internet]. [cited 29 Jan 2024]. Available: https://rethinkpriorities.org/

9. Browning H. The measurability of subjective animal welfare. J Conscious Stud. 2022;29: 150–179.

10. Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York.: MacMillan; 2011. pp. 445–446.

11. Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72: 429–445.

12. EQ-5D instruments. [cited 21 Sep 2023]. Available: https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/

13. Gómez-Emilsson. Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain. In: Qualia Research Institute. 2019, Aug 10.

14. Gómez-Emilsson A, Percy C. The Heavy-Tailed Valence Hypothesis: The human capacity for vast variation in pleasure/pain and how to test it. Pre-print. 2022. doi:10.31234/osf.io/krysx

15. Fredrickson BL, Kahneman D. Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65: 45–55.

16. Kahneman D, Fredrickson BL, Schreiber CA, Redelmeier DA. When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End. Psychol Sci. 1993;4: 401–405.

17. Müller UWD, Gerdes ABM, Alpers GW. Time is a great healer: peak-end memory bias in anxiety–induced by threat of shock. Behav Res Ther. 2022;159: 104206.

18. Redelmeier DA, Katz J, Kahneman D. Memories of colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Pain. 2003;104: 187–194.

19. Lai KC, Provenzale JM, Delong D, Mukundan S Jr. Assessing patient utilities for varying degrees of low back pain. Acad Radiol. 2005;12: 467–474.

20. Wetherington S, Delong L, Kini S, Veledar E, Schaufele MK, McKenzie-Brown AM, et al. Pain quality of life as measured by utilities. Pain Med. 2014;15: 865–870.

21. Carvalho B, Hilton G, Wen L, Weiniger CF. Prospective longitudinal cohort questionnaire assessment of labouring women’s preference both pre- and post-delivery for either reduced pain intensity for a longer duration or greater pain intensity for a shorter duration. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113: 468–473.

22. Wallenstein SL, Heidrich G 3rd, Kaiko R, Houde RW. Clinical evaluation of mild analgesics: the measurement of clinical pain. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;10 Suppl 2: 319S–327S.

23. Cecchi GA, Huang L, Hashmi JA, Baliki M, Centeno MV, Rish I, et al. Predictive dynamics of human pain perception. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8: e1002719.

24. Stevens SS. On the psychophysical law. Psychol Rev. 1957;64: 153–181.

25. Stevens SS. Cross-modality validation of subjective scales for loudness, vibration, and electric shock. J Exp Psychol. 1959;57: 201–209.

26. Price DD, McHaffie JG, Larson MA. Spatial summation of heat-induced pain: influence of stimulus area and spatial separation of stimuli on perceived pain sensation intensity and unpleasantness. J Neurophysiol. 1989;62: 1270–1279.

27. Baliki MN, Geha PY, Apkarian AV. Parsing pain perception between nociceptive representation and magnitude estimation. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101: 875–887.

28. Jensen MP, Smith DG, Ehde DM, Robinsin LR. Pain site and the effects of amputation pain: further clarification of the meaning of mild, moderate, and severe pain. Pain. 2001;91: 317–322.

29. Cleeland CS. The impact of pain on the patient with cancer. Cancer. 1984;54: 2635–2641.

30. Rainville P, Feine JS, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. A psychophysical comparison of sensory and affective responses to four modalities of experimental pain. Somatosens Mot Res. 1992;9: 265–277.

31. Vowles KE, McNeil DW, Sorrell JT, Lawrence SM. Fear and pain: investigating the interaction between aversive states. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115: 821–833.

32. Gentle MJ. Attentional Shifts Alter Pain Perception in the Chicken. Anim Welf. 2001;10: 187–194.

33. Ossipov MH, Dussor GO, Porreca F. Central modulation of pain. J Clin Invest. 2010;120: 3779–3787.

34. Mogensen A. Welfare and felt duration (Andreas Mogensen). Global Priorities Institute Working Paper Series. 2023;14-2023. Available: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/2MHpzN33bmqm2BHwJ/welfare-and-felt-duration-andreas-mogensen

35. Schukraft J. Differences in the Intensity of Valenced Experience across Species. Rethink Priorities; 2020. Available: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/H7KMqMtqNifGYMDft/differences-in-the-intensity-of-valenced-experience-across

36. Fischer B. An Introduction to the Moral Weight Project. Rethink Priorities; 2022. Available: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/hxtwzcsz8hQfGyZQM/an-introduction-to-the-moral-weight-project

37. Schukraft J. The subjective experience of time: welfare implications. Rethink Priorities; 2020 Jul. Available: https://rethinkpriorities.org/publications/the-subjective-experience-of-time-welfare-implications

38. Schukraft J. Does Critical Flicker-Fusion Frequency Track the Subjective Experience of Time? Rethink Priorities; 2020. Available: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/DAKivjBpvQhHYGqBH/does-critical-flicker-fusion-frequency-track-the-subjective

39. McCarberg B, Peppin J. Pain Pathways and Nervous System Plasticity: Learning and Memory in Pain. Pain Med. 2019;20: 2421–2437.

40. Page GG, Ben-Eliyahu S. The immune-suppressive nature of pain. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1997;13: 10–15.

41. Singer P. Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals. New York review; 1975.

42. Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ. Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens. A blueprint for the comparative analysis of welfare in animals (https://tinyurl.com/amazon-pain). 2021.

43. Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ, editors. Quantifying Pain in Broiler Chickens: Impact of the Better Chicken Commitment and Adoption of Slower-Growing Breeds on Broiler Welfare. Independently published. https://tinyurl.com/bookhens; 2022.

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Confounding Factors in Welfare Comparisons of Animal Production Systems Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable

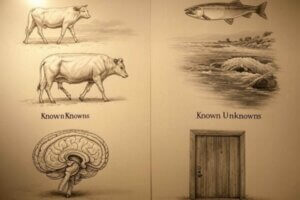

Borrowing the Knowns and Unknowns Framework to Reveal Blind Spots in Animal Welfare Science Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim There is always a risk of fixating on what we already