Defining Affective Experiences

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim

Defining pain has long been a subject of debate. Recently, a new and substantially modified definition was published by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (Raja et al., 2020). In this more recent version, pain is defined as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” This definition is expanded by the addition of six key notes:

We argue that the IASP’s definition of pain fails to fully encompass its evolutionary, cognitive, and affective dimensions. It overlooks key aspects of this sensory phenomenon, such as its inherent consciousness, its independence from learning, and its evolutionary role extending beyond mere avoidance of tissue damage – when what should be considered is fitness damage. The definition is also overly human-centric. For example, the note that a person’s report of an experience as pain should be respected ignores the weak association between pain indicators and self-reports (Labus, Keefe and Jensen, 2003). Assuming greater validity of self-reports relative to objective indicators of pain is also detrimental to the advancement of pain assessment in non-verbal subjects.

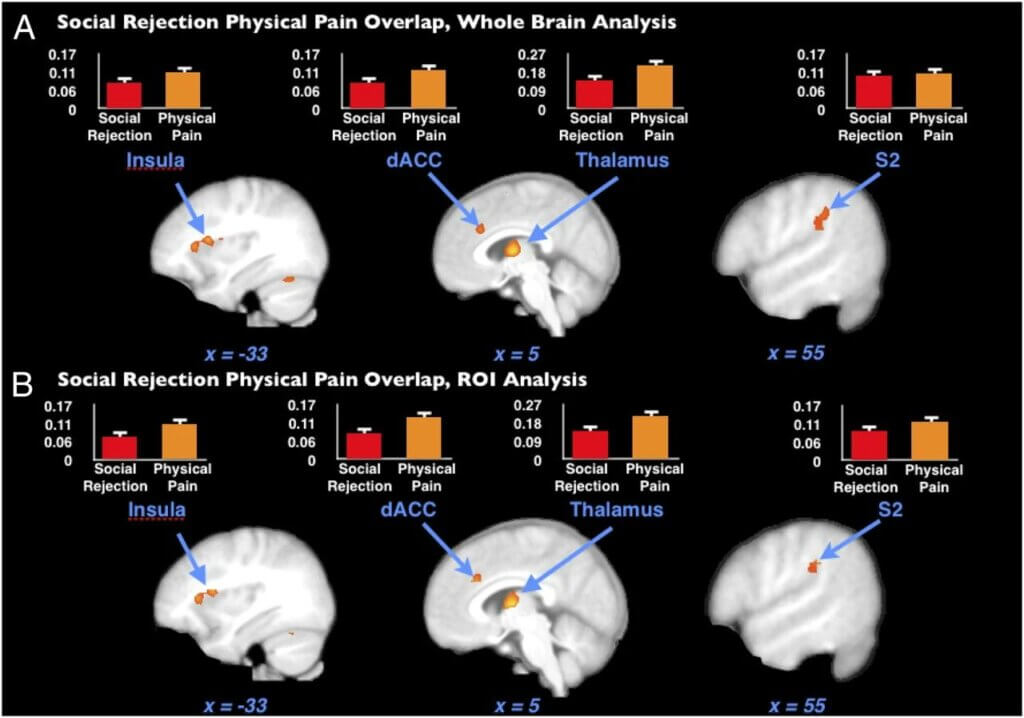

We further argue that the definition should acknowledge the multidimensional and dynamic (temporally varying) nature of pain, and allow for both physical and psychological categorizations. While there is often a reluctance to extend the term ‘pain’ beyond the realm of tissue damage or sensations processed by pain receptors, it is important to recognize that the experience of pain originates in the brain and can emerge independently of these receptors. The sensation of pain, likely evolved originally to process information from these receptors, has been co-opted evolutionarily to signal other threats to the organism beyond physical tissue damage. Accordingly, evidence indicates the similar processing of emotional and physical pain in the brain (Kross et al., 2011), and the commonalities of their neural pathways (Sturgeon and Zautra, 2016), with psychological and physical pain engaging similar brain regions (Figure 1) and involving similar neurochemicals, such as opioids. Jaak Panksepp, the father of affective neuroscience, indeed used the term ‘psychological pain’ to describe emotional states associated with two primary systems, ‘PANIC/GRIEF’ and ‘FEAR’. This sub-classification of pain as “physical” and “psychological” recognizes these evolutionary and neuroanatomical commonalities.

Figure 1. Emotional and physical pain activate very similar brain regions (from: Kross, E. et al. 2011, Social rejection shares somatosensory representations with physical pain, PNAS, 108, 6270–6275). https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1102693108

In an effort to address these shortcomings, we propose the following alternative definition:

Pain is a conscious experience, evolved to elicit corrective behavior in response to actual or imminent damage to an organism’s survival and/or reproduction. Still, some manifestations, such as neuropathic pain, can be maladaptive. It is affectively and cognitively processed as an adverse and dynamic sensation that can vary in intensity, duration, texture, spatial specificity, and anatomical location. Pain is characterized as ‘physical’ when primarily triggered by pain receptors and as ‘psychological’ when triggered by memory and primary emotional systems. Depending on its intensity and duration, pain can override other adaptive instincts and motivational drives and lead to severe suffering.

The proposed definition addresses the following points:

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Confounding Factors in Welfare Comparisons of Animal Production Systems Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable

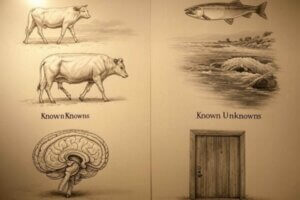

Borrowing the Knowns and Unknowns Framework to Reveal Blind Spots in Animal Welfare Science Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim There is always a risk of fixating on what we already