Defining Affective Experiences

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Implications for refining Cumulative Pain estimates and for determining the potential for positive welfare

Cynthia Schuck-Paim and Wladimir J Alonso

“Is a chameleon having two thoughts simultaneously as one eye focuses on a juicy grasshopper on the neighboring twig while the other eye searches the branches overhead for a better approach route? Can a seahorse ogle a potential mate with one eye while tracking the movements of a lurking predator with the other? My single-track brain can’t. If I read the newspaper while the radio plays ‘This American Life’, my mind can toggle back and forth between the two, but try as I might I cannot stream both stories at the same instant.”

Jonathan Balcombe (What a Fish Knows)

The possibility of genuinely experiencing multiple stimuli, thoughts or affective states simultaneously is a contentious topic. While one view holds that it is possible to multitask and attend to multiple stimuli in a parallel manner, another holds that what one may feel as attention to multiple stimuli in fact involves switching among them very rapidly, in a serial manner [1]. The latter view is consistent with theories that compare conscious awareness to a spotlight in a dark room, where the spotlight represents the focus of one’s awareness, and the dark room encompasses all sensory inputs, perceptions, memories, and affective states immediately available. Like a moving flashlight, it illuminates one experience at a time [2,3].

This scientific debate holds significance for assessments of animal welfare, as assumptions about how concurrent affective states (positive or negative) permit, exclude, or modulate one another can critically affect estimates of the actual times experienced in the affective states examined. This is especially true if we consider that organisms may frequently experience welfare challenges that overlap in time. Here we explore the role of attention on affective experiences within the context of ‘Cumulative Pain’ assessments [4] (where pain is used as a shorthand for any negative affective experiences).

For instance, consider a hypothetical scenario where an individual is exposed, in one day, to two consecutive sources of Hurtful pain for five hours each. In this case, Cumulative time in pain would be represented by 10 hours. But if the two pain episodes unfolded simultaneously, would Cumulative Pain still be best represented by 10 hours? And during the five hours of simultaneous exposure to these two pain sources, would there be any time left for positive experiences? Would this change if the second source of pain was of a different intensity (e.g., Annoying)?

So far, estimates of Cumulative Pain have been based on the operational assumption that multiple concurrent challenges have the above mentioned additive effect on experience (namely that their effects when experienced simultaneously are best represented by the sum of their isolated effects). This solution works well for the purpose of distinguishing the impact of welfare challenges across scenarios or production systems [5,6]. However, to the extent that attention is selective, switching among simultaneously occurring experiences, estimates of cumulative time in pain can be refined to incorporate this phenomenon. Such a refinement should enable estimating the time individuals are aware of and focused on each negative experience (as opposed to simply being exposed to them). Additionally, it allows exploring the time that remains available for individuals to enjoy positive affective experiences, once the time actually preoccupied with ‘pain’ is properly discounted.

ATTENTION AS A LIMITED RESOURCE

The dynamic nature of attention plays a critical role in our affective experiences. Our affective states are not static, instead fluctuating as our attention shifts between various aspects of a situation, memory, or sensory input. This continuous shift in attention leads to the processing and prioritization of different emotions or emotional cues at different points in time.

The involuntary capture of attention by pain is a crucial aspect of its role as a warning signal of (real or perceived) danger. Pain demands attention, as it must change behavior to prevent survival and reproduction from being compromised [7–10]. In general, the greater the threat, the more intense the pain signal [11,12], engaging more of the individual’s attention [10,12–15].

Attention is, however, a limited resource, constrained by the brain’s architecture, its finite capacity for neural processing and limited supply of energy. Amidst the constant influx of vast amounts of sensory data, various mechanisms evolved to direct the brain’s attention to relevant information, while suppressing less relevant stimuli. For example, top-down mechanisms of attentional control are driven by an individual’s goals and expectations (e.g., if an individual is searching for red food, these mechanisms will enhance the processing of red stimuli while suppressing other colors) [16,17]. Allocation of attention is also determined by bottom-up saliency mechanisms that are triggered by the inherent features of stimuli, particularly their intensity, novelty, or contrast [18]. Sensory processing areas respond more robustly to more intense, contrasting and novel stimuli, and this enhanced activity increases the likelihood that these stimuli are attended to [19].

The perception of pain, both physical and psychological, is closely intertwined with these attentional processes. Pain’s ability to capture attention is also largely mediated by bottom-up saliency mechanisms triggered by the inherent features of the painful experience, such as their intensity or sudden onset. For example, in the case of physical pain, as intensity increases, nociceptors transmit more frequent and larger electrical signals along the pain-processing pathway, triggering the release of greater amounts of neurotransmitters like glutamate (a primary excitatory neurotransmitter) and neuromodulators like substance P (involved in pain transmission and sensitization of nociceptors). This, in turn, intensifies the activation of pain-processing neurons and amplifies pain signals within the neural network, capturing more attention to ensure that organisms respond adequately [20,21] .

Pain is also modulated by voluntary mechanisms such as attentional focus [22]. Consciously directing attention towards a painful stimulus can increase the perception of pain intensity, given the heightened awareness of the pain sensation and the amplification of emotional components of pain, such as anxiety or distress [23,24]. Conversely (and this is also of great relevance to strategies to improve animal welfare), reduced pain is observed if attention is directed away from the painful stimuli by more salient experiences (e.g., fear, stress, highly motivated tasks) [21]. By occupying the brain’s limited attentional resources with alternative tasks or stimuli, the processing of pain signals is inhibited, leading to a reduction in pain perception.

“As Hippocrates long ago observed, if two pains are felt at the same time, the severer one dulls the other.”

Charles Darwin (The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals)

A natural conclusion from the previous section is that when individuals are exposed to simultaneous pain sources that differ in their salience, the brain will prioritize processing of the more salient one (i.e., more intense, novel or threatening), devoting a greater share of its limited attentional resources.

Top-down mechanisms can also lead to inhibition of concurrent, less salient, pain. One such mechanism is known as conditioned pain modulation (CPM), or ‘diffuse noxious inhibitory control’ (a term used more often in animal research), sometimes described as ‘pain inhibits pain’ [25]. CPM occurs when response from a painful stimulus is inhibited by another, often spatially distant noxious stimulus. The process involves the activation of descending inhibitory pathways that can reduce the activity of pain-transmitting neurons in the spinal cord. One means whereby this modulation happens is through the release of endogenous opioids, which inhibit the release of neurotransmitters (e.g., substance P, glutamate) needed for pain transmission. Engagement in pleasant and highly motivated activities and movement may also trigger the release of endogenous opioids, as well as other neurochemicals like dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin, which can too contribute to a reduced perception of pain. Additionally, a strong painful experience may also serve as an anchor or comparison point by which others are judged (hence reducing their intensity relative to when they are judged individually) [26]

If less intense pain is nearly overshadowed by more intense pain, then the experience of simultaneous pain cannot be represented by the sum of the experience of each pain stimulus when experienced alone. High intensity pain will likely eliminate less intense pain during those moments when attention is recruited to the former.

For the purposes of Cumulative Pain analysis, and until further knowledge is available, we therefore assume that when an individual experiences pain episodes of different intensities concurrently, only the most intense pain should be computed.

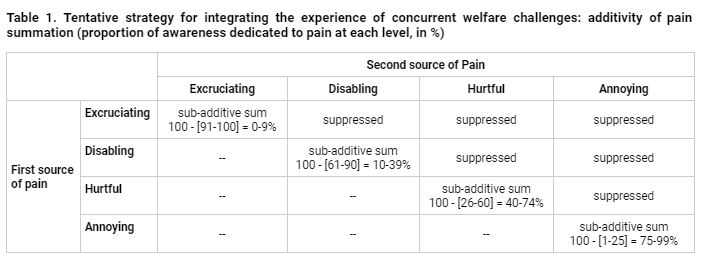

With concurrent pain of similar intensity a more nuanced strategy is required. In line with observations that increasing the area of exposure to noxious stimuli produces a disproportionately small (sub-additive) increase in the perceived intensity of pain [27], we consider the possibility that for pain of similar intensity, the share of attention devoted to the experience is summated in a sub-additive way. The extent to which summation is sub-additive is, however, unclear. As a starting point for further investigation and debate, we consider two scenarios:

Because pain of greater intensities demands a greater share of the organism’s attention, remaining attentional resources for the processing of additional pain would become progressively scarcer. A tentative set of estimates for the degree of attention allocated to each intensity category is as follows: (1) Excruciating: 91-100%, (2) Disabling: 61-90%, (3) Hurtful: 26-60%, (4) Annoying: 1-25%. In Table 1, these estimates are used to suggest the extent to which sub-additivity is expected with simultaneous sources of similarly intense pain in each case.

For example, in the case of Excruciating pain, these thresholds would suggest that when a second source of Excruciating pain is experienced simultaneously, the maximum increase in the time attending to the new source of pain (in addition to that grabbed by an isolated source of Excruciating pain) would be 9%. Conversely, if two sources of Annoying pain are experienced simultaneously, there would be near complete additivity (70-99%).

One obvious limitation of this approach is our current lack of evidence on the share of attention associated with each level of pain intensity (i.e. the validity of estimates in Table 1). Another limitation is the fact the proportion of attention allocated to each intensity category cannot be equated to its degree of unpleasantness. Consider this scenario as an example: two individuals are enjoying a pleasant conversation in a park. Suddenly, one is bitten by a mosquito. The discomfort experienced is just Annoying, capturing approximately 10% of the individual’s attention. Now imagine that a dozen additional mosquitoes begin to bite this person, causing their attention to become almost entirely focused on attempting to shoo the insects away and scratching the bites. The conversation in the park is no longer feasible. In this scenario, nearly all attention was focused on this experience. Although the unpleasantness of the experience increased, it is not possible to say that the intensity of the overall pain increased proportionally to the attention it demanded as the number of mosquitoes grew, becoming Hurtful. Pain intensity and pain-related attention are related but separate aspects of the pain experience. Pain intensity refers to the magnitude of the unpleasant sensory and emotional experience. Pain-related attention, on the other hand, refers to the extent to which an individual’s cognitive resources are directed towards or distracted by the pain.

The second scenario adopts a simpler analytical approach, whereby each subsequent source of pain is assigned a progressively smaller increase in perceived intensity, with the second source contributing a 50% increase, the third source a 25% increase, and so on progressively. As before, in the Cumulative Pain framework such increases are translated into a greater share of time attending to pain of that intensity.

Again, these proposed values are only provisional and should be considered as a simplified starting point given our limited understanding of pain and attention mechanisms, and the many potentially confounding factors in this analysis. For example, attention to pain will be also influenced by the presence of additional stimuli competing for attention, differences in the discriminatory properties of the pain sources, and variability in pain thresholds and coping mechanisms. Thus, the proposed values are unlikely to be universally applicable.

The Cumulative Pain framework estimates the time individuals typically spend with pain of each intensity category. Thus, one hour of Hurtful pain means that an individual was exposed to a source of Hurtful pain for one hour. In its current form, the framework represents two simultaneous sources of Hurtful pain, each lasting an hour, as two hours of Hurtful pain. This choice offers the benefit of simplicity, and eliminates the need for more complex assumptions about the type of additivity in the subjective perception of pain, for which knowledge is not yet available.

However, estimates computed in this manner often raise the question of how an individual can experience more hours of pain than there are hours in a day, or even a lifetime. For instance, consider a fictitious case: an animal spends her life with two ailments: (1) a mild “itch” (of an Annoying intensity) and (2) a mild thermal discomfort (of an Annoying nature too). She lives for 60 weeks, and pain is only felt when awake (16 hours/day, totaling 6,720 hours awake). In this case, she experiences 6,720 hours of Annoying pain due to the itch and 6,720 hours of Annoying pain due to thermal discomfort. The total of 13,440 hours of Annoying pain is longer than her life. This is a by-product of a technical choice in the approach, but one that may confuse the audience.

One potential solution to this issue involves incorporating the degree of attention allocated to each pain intensity category into Cumulative Pain calculations. In other words, instead of estimating the duration an individual is subjected to pain (i.e., the entire period during which an individual is exposed to an unpleasant experience), one would estimate the time spent attending to pain, namely the duration of those moments an individual actively focuses on or is aware of this sensation. This latter time estimate will be typically shorter, as individuals may not be continuously aware of their discomfort or may actively choose to focus on other aspects of their experience part of the time.

For instance, if we assume that an individual is aware of Annoying pain only 25% of the time, then each hour of Annoying pain exposure should be converted into a maximum of 15 minutes of actual time spent in Annoying pain. Consequently, two simultaneous sources of annoying pain lasting one hour would be translated into a maximum of 30 minutes of annoying pain (following strategy A in the previous section) or 22.5 minutes of annoying pain (strategy B).

By incorporating attention allocation into the framework, we can more accurately estimate the actual time spent aware of a negative affective state. This resolves the apparent contradiction of cumulative pain estimates exceeding a lifetime. However, the decision to incorporate this refinement depends on the reliability of estimates for the share of attention allocated to painful experiences of varying intensities. Adopting provisional values that may change in the future could harm the comparability of analytical results. Therefore, we greatly appreciate any feedback and input that can help inform our decision-making in this regard.

Although, in our view, negative affective states (particularly more extreme forms) have a larger impact on well-being (e.g., improvements in positive states are frequently bounded and lost to hedonic adaptation, whereas adaptation to pain is unlikely; [28]), it is also important to consider how concurrent experiences of different valence may affect each other. In this regard, it is reasonable to assume that positive welfare is precluded, either partially or completely, in animals experiencing negative affective states, particularly the more intense ones. This assumption is in fact part of the defining criteria of the four intensity categories considered in the Cumulative Pain framework.

We propose that the amount of time individuals spend focusing on pain determines the time remaining for the experience of positive states. Thus, ‘potential for positive welfare’ can be defined as the estimated time available to enjoy positive affective experiences once the time spent in pain has been discounted. We purportedly use the term ‘potential’ since the absence of suffering both allows for a state of neutral welfare (something that by itself could be considered good) and for experiences of positive valence (e.g. enjoyment or pleasure), equated to good welfare by some authors [29].

Some practical limitations must be highlighted in this exercise. Again, as discussed, empirical evidence is still lacking on the extent to which pain of different intensities differentially demands attention. Importantly, estimating the potential for positive welfare requires considering all time in negative affective states. In other words, it is necessary to take into account every single challenge to which individuals are exposed. If only a subset of challenges is considered, the time available for neutral or positive welfare may be largely overestimated.

Additionally, the potential for positive welfare may be also overestimated if factors other than attention are not considered. For example, pain caused by traumatic injury or pathological processes may lead to immobility, restricted movement or impaired behavioral responsiveness to potentially pleasurable opportunities [30]. Similarly, sickness, weakness, nausea, dizziness and other debilitating affects may demotivate animals from engaging in physically active, gregarious and positive behaviors [30].

Finally, positive and negative affective states may interact in complex ways other than those considered. For instance, evidence indicates that in environments where animals can engage in motivated behaviors the perceived intensity of pain is reduced. In chickens, experiments conducted by Mike Gentle two decades ago [21,31] have shown that the higher the motivation to engage in a behavior (hence attention diverted to it), the higher the degree of endogenous analgesia mediated by opioids. The possibility to express positive behaviors may therefore inhibit pain that would otherwise be felt as Hurtful or Annoying (pain of higher intensity cannot, by definition, be eliminated with distraction).

Understanding the role of attention in the perception of concurrent negative affective states is crucial for refining estimates of cumulative time in pain and animal welfare assessments. Taking the temporal synchronicity of the various welfare challenges animals experience into account is also necessary to determine the potential for positive welfare — the time available for animals to experience positive affective states once the time spent in pain has been discounted.

As an immediate step to refine estimates of Cumulative Pain, we suggest that when individuals experience pain of different intensities simultaneously, the most intense pain is likely to capture most of the individual’s attention, overshadowing less intense pain.

When it comes to concurrent pain of similar intensity, the degree to which pain summation is sub-additive is an important aspect to consider. The analytical strategies presented here are meant only as a starting point for research and debate in this area. They depend critically on acquiring more knowledge about the share of attention demanded by pain of varying intensities. More evidence in this regard is also needed to determine, more rigorously, the actual time spent aware of and focused on pain, which in turn resolves the apparent contradiction of cumulative pain estimates surpassing a lifetime.

1. Sigman M, Dehaene S. Brain mechanisms of serial and parallel processing during dual-task performance. J Neurosci. 2008;28: 7585–7598.

2. Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Q J Exp Psychol. 1980;32: 3–25.

3. Jaynes J. The origin of consciousness in the breakdown of the bicameral mind. Leonardo. 1980;13: 157.

4. Alonso WJ, Schuck-Paim C. The Comparative Measurement of Animal Welfare: the Cumulative Pain Framework. In: Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ, editors. Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens. Independently published. https://tinyurl.com/bookhens; 2021.

5. Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ, editors. Quantifying Pain in Broiler Chickens: Impact of the Better Chicken Commitment and Adoption of Slower-Growing Breeds on Broiler Welfare. Independently published. https://tinyurl.com/bookhens; 2022.

6. Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ. Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens. A blueprint for the comparative analysis of welfare in animals (https://tinyurl.com/amazon-pain). 2021.

7. Panksepp J. Affective neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press Affective neuroscience; 1998.

8. Cervero F. Understanding Pain: Exploring the Perception of Pain. MIT Press; 2012.

9. Sneddon LU, Elwood RW, Adamo SA, Leach MC. Defining and assessing animal pain. Anim Behav. 2014;97: 201–212.

10. Solms M. The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. W. W. Norton & Company; 2021.

11. Merker B. Drawing the line on pain. Animal Sentience: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Animal Feeling. 2016;1: 23.

12. Mellor DJ, Beausoleil NJ, Littlewood KE, McLean AN, McGreevy PD, Jones B, et al. The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human-Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare. Animals (Basel). 2020;10. doi:10.3390/ani10101870

13. Rowan AN. Refinement of Animal Research Technique and Validity of Research Data. Toxicol Sci. 1990;15: 25–32.

14. Barclay RJ, Herbert WJ, Poole T. The disturbance index : a behavioural method of assessing the severity of common laboratory procedures on rodents. UFAW, Universities Federation for Animal Welfare; 1988.

15. Eccleston C, Crombez G. Pain demands attention: a cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychol Bull. 1999;125: 356–366.

16. Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3: 201–215.

17. Treue S. Visual attention: the where, what, how and why of saliency. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13: 428–432.

18. Itti L. CHAPTER 94 – Models of Bottom-up Attention and Saliency. In: Itti L, Rees G, Tsotsos JK, editors. Neurobiology of Attention. Burlington: Academic Press; 2005. pp. 576–582.

19. Serences JT, Yantis S. Selective visual attention and perceptual coherence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10: 38–45.

20. Kahneman D. Attention and Effort. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1973.

21. Gentle MJ. Attentional Shifts Alter Pain Perception in the Chicken. Anim Welf. 2001;10: 187–194.

22. Weary DM. Suffering, Agency, and the Bayesian Mind. In: McMillan FD, editor. Mental Health and Well-being in Animals. CAB International; 2020. pp. 156–166.

23. Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14: 502–511.

24. Garland EL. Pain processing in the human nervous system: a selective review of nociceptive and biobehavioral pathways. Prim Care. 2012;39: 561–571.

25. Sirucek L, Ganley RP, Zeilhofer HU, Schweinhardt P. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls and conditioned pain modulation: a shared neurobiology within the descending pain inhibitory system? Pain. 2023;164: 463.

26. Lautenbacher S, Prager M, Rollman GB. Pain additivity, diffuse noxious inhibitory controls, and attention: a functional measurement analysis. Somatosens Mot Res. 2007;24: 189–201.

27. Adamczyk WM, Manthey L, Domeier C, Szikszay TM, Luedtke K. Spatial summation of pain increases logarithmically. bioRxiv. 2020. p. 2020.06.30.179556. doi:10.1101/2020.06.30.179556

28. Kahneman D, Krueger AB. Developments in the Measurement of Subjective Well-Being. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20: 3–24.

29. Mellor DJ. Enhancing animal welfare by creating opportunities for positive affective engagement. N Z Vet J. 2015;63: 3–8.

30. Mellor DJ. Updating Animal Welfare Thinking: Moving beyond the “Five Freedoms” towards “A Life Worth Living.” Animals (Basel). 2016;6. doi:10.3390/ani6030021

31. Hocking PM, Robertson GW, Gentle MJ. Effects of anti-inflammatory steroid drugs on pain coping behaviours in a model of articular pain in the domestic fowl. Res Vet Sci. 2001;71: 161–166.

32. Alonso WJ, Schuck-Paim C. Pain-Track: a time-series approach for the description and analysis of the burden of pain. BMC Research Notes. 2021;14: 229. https://rdcu.be/cl0kD.

The content of this discussion was inspired by various (very pertinent) questions about the method raised by Michael St. Jules.

How to Define Affective Experiences for Analysis: Striking the Right Level of Detail Cynthia Schuck-Paim & Wladimir Alonso The Welfare Footprint Framework (WFF) is designed to quantify the welfare impact

Confounding Factors in Welfare Comparisons of Animal Production Systems Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim Controlled experiments—where variables are deliberately manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships—are the gold standard for drawing reliable

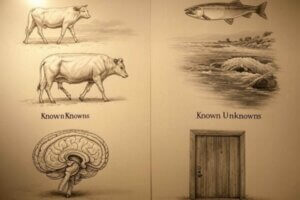

Borrowing the Knowns and Unknowns Framework to Reveal Blind Spots in Animal Welfare Science Wladimir J Alonso, Cynthia Schuck-Paim There is always a risk of fixating on what we already